Wifi speeds vs. broadband speeds: Wifi speeds have lagged behind ever increasing Internet speeds. As a result, there has been a very rapid switch in wifi from Wi-Fi 4 (2.4 GHz 802.11n) to Wi-Fi 5 (5 GHz 802.11ac), to Wi-Fi 6 (5 GHz 802.11ax), and now to Wi-Fi 6E (802.11ax extended into 6 GHz) in an attempt to keep up (and Wi-Fi 7 is just around the corner). ★ So what new router/AP should you consider buying today? Router Manufacturers' Marketing Hype: Don't be fooled by the marketing hype of router manufacturers' advertising outrageously high aggregate (all bands added together) Gbps wireless speeds (like 7.2 Gbps). What really matters is realistic speeds achieved by your wifi client devices, that actually exist today. The weakest link: Wifi throughput to a Wi-Fi 5 wireless client device will likely max out at around 600 Mbps (±60 Mbps) for 2x2 MIMO no matter what 4×4 router is used (when right next to the router and slower at distance). And the far majority of ALL wireless client devices today (smartphones, tablets, laptops, etc) are still only 2x2 MIMO. So your client device is almost certainly causing slow wifi speeds (and maybe not your existing AP/router). The best router/AP value today: A mid-range Wi-Fi 6 router supporting (1) 4×4 MIMO, (2) ALL DFS channels, and (3) beamforming is a great value today (as of April 2023; best seen upper right). So, upgrade, or not?: The only question that really matters is: What are client PHY speeds now and what will client PHY speeds be after an AP/router update? Because, if (the majority of) client PHY speeds will not increase after a router update (especially for 'at range' client devices), what is the point in spending money on a new router that won't improve Wi-Fi speeds?

The goal of this paper: This paper was written to help people understand current wifi technology, so that YOU can make an educated 'router' upgrade decision -- because there is WAY too much hype out there (especially about wifi speeds) -- and router manufacturers' are directly to blame. The issue: Wifi spectrum is a limited, TIME-shared resource. Any number of access points (both yours and neighbors) can all share the SAME wifi spectrum. But because wifi use has exploded over the last few years (tablets, laptops, smartphones, TVs, Blu-rays, security cams, thermostats, Bluetooth, BLE, Zigbee, microwaves, etc) the wifi spectrum is way overcrowded. And when combined with ISP Internet speeds now often many times faster than Fast Ethernet (100Mbps), and sometimes even 1 Gbps, wifi speeds have not kept up.

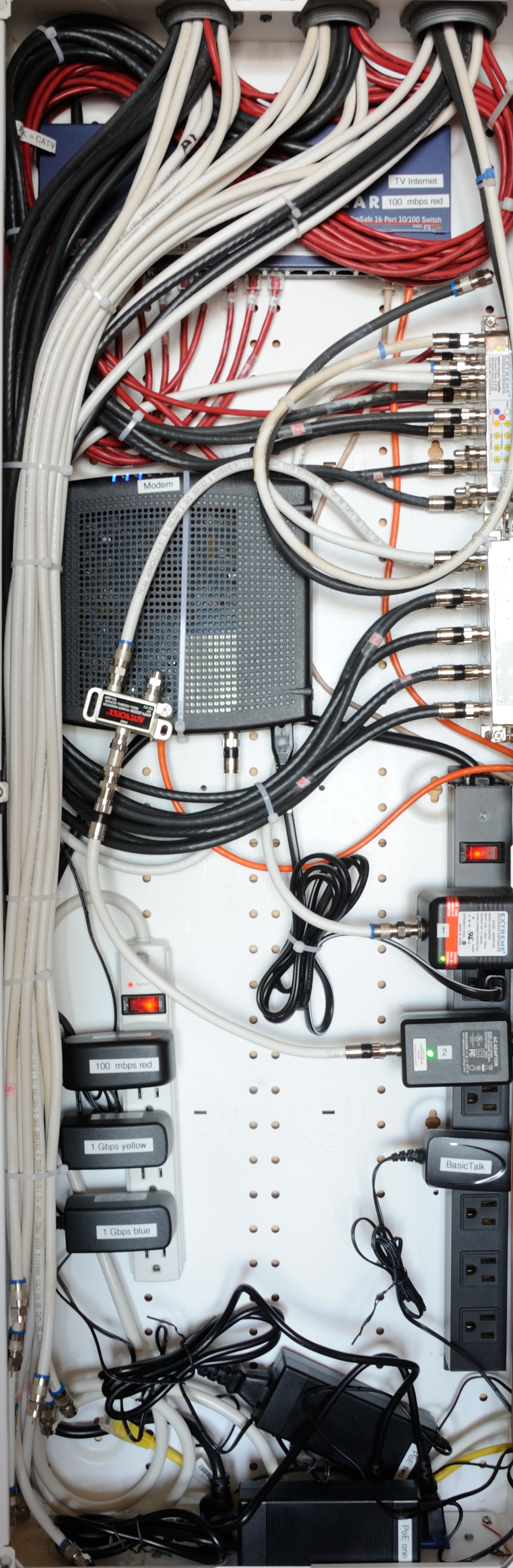

Industry solution: The industry quickly switched to the much newer Wi-Fi 6 (5 GHz 802.11ax) spectrum, where speeds are much faster, due to more available spectrum and new wifi features, such as MIMO and wider (up to 160 MHz) channels. But that requires a new router, but which one? BUT, our devices are still speed limited. Why? As will be shown in the next sections, mainly due to limited 2×2 MIMO support in almost all of today's wireless (and battery powered) client devices. But let's also be very realistic. If you have 400 Mbps (or less) Internet speeds, 2×2 MIMO Wi-Fi 5 to your router is almost always sufficient -- and IS fast enough -- even with an older high quality "wave 2" 4×4 MIMO 802.11ac router (an example of one is seen right).

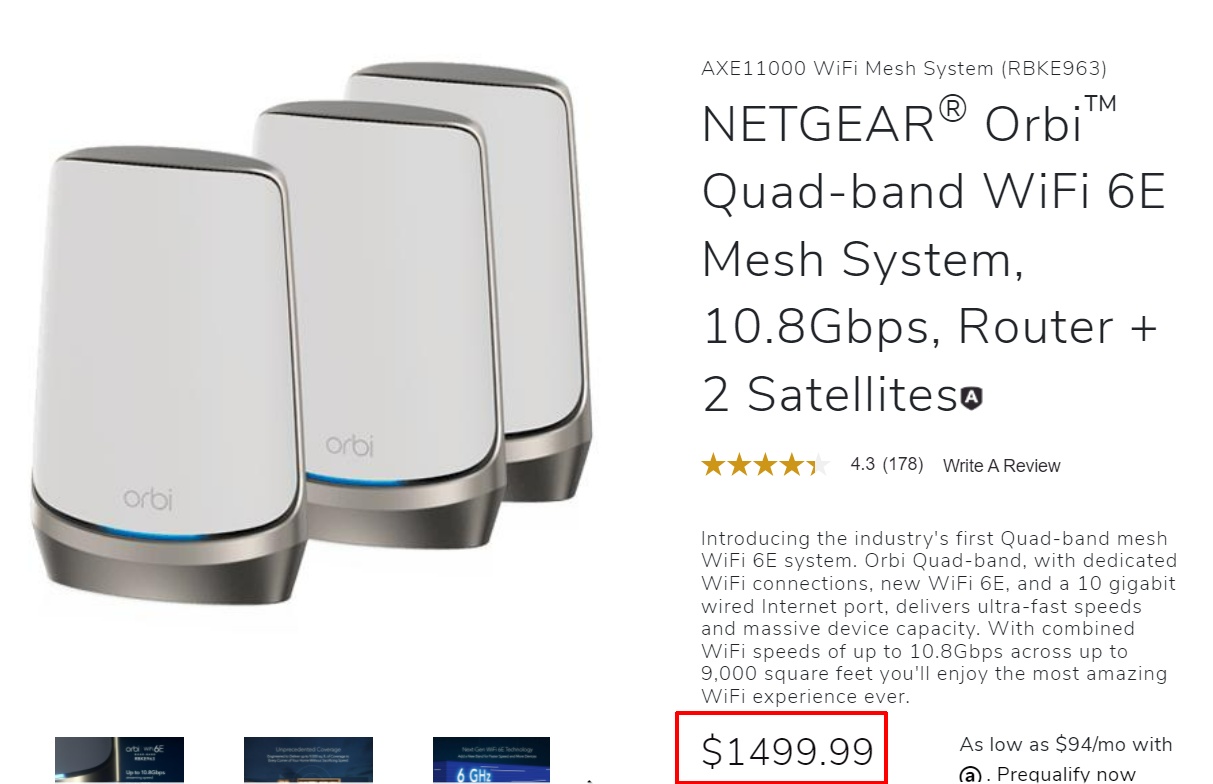

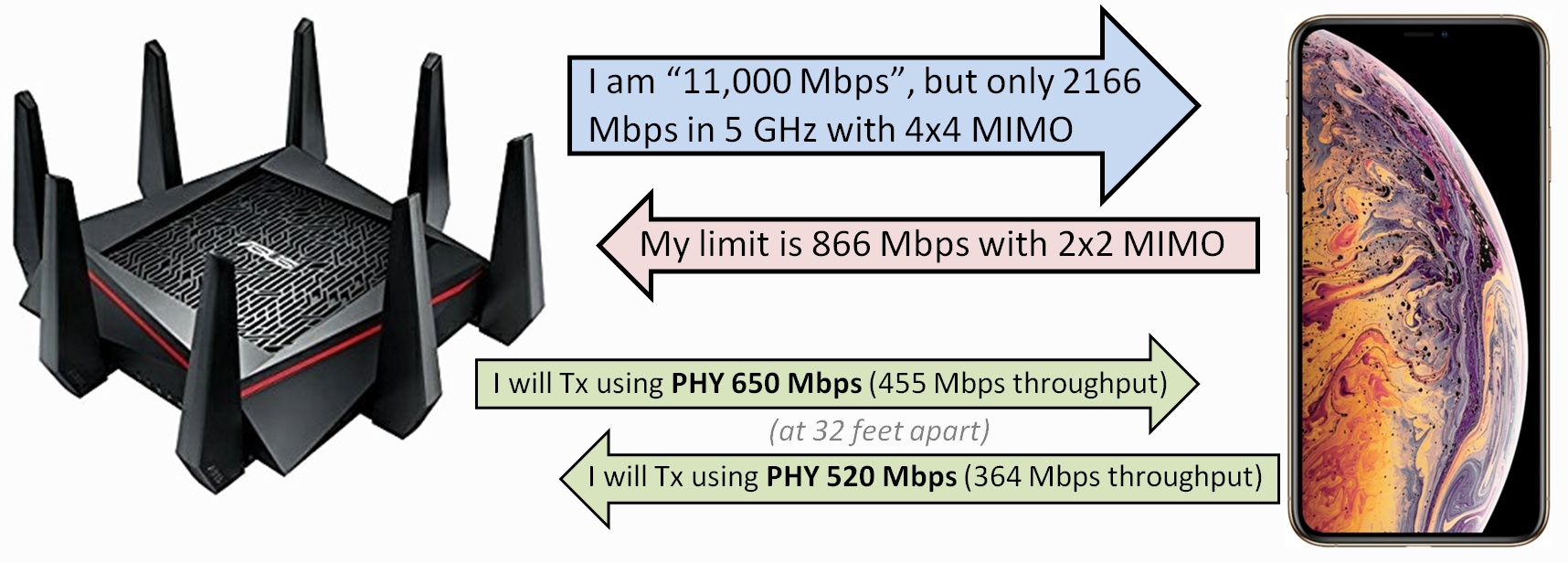

In summary: Wi-Fi can only operate as fast as the least capable Wi-Fi device in a 'conversation', which almost always is your client device (and not the router). KEY Wi-Fi concept: Client devices often limit speeds, not the router/AP. The weakest link in Wi-Fi is YOUR client device: You have 1 Gbps Internet, and just bought a very expensive AX11000 class router with advertised speeds of up to 11 Gbps, but when you run a speed test from your iPhone XS Max (at a distance of around 32 feet), you only get around 450 Mbps (±45 Mbps). Same for iPad Pro. Same for Samsung Galaxy S8. Same for a laptop computer. Same for most wireless clients. Why? Because that is the speed expected from these (2×2 MIMO) devices! This section explains in great detail exactly why that is. You may safely skip to the next section for a shortcut if this section is too detailed/technical for you. The rest of this section is a "deep dive" into everything that limits speed when a Wi-Fi 5 client device communicates with a Wi-Fi 5 router.

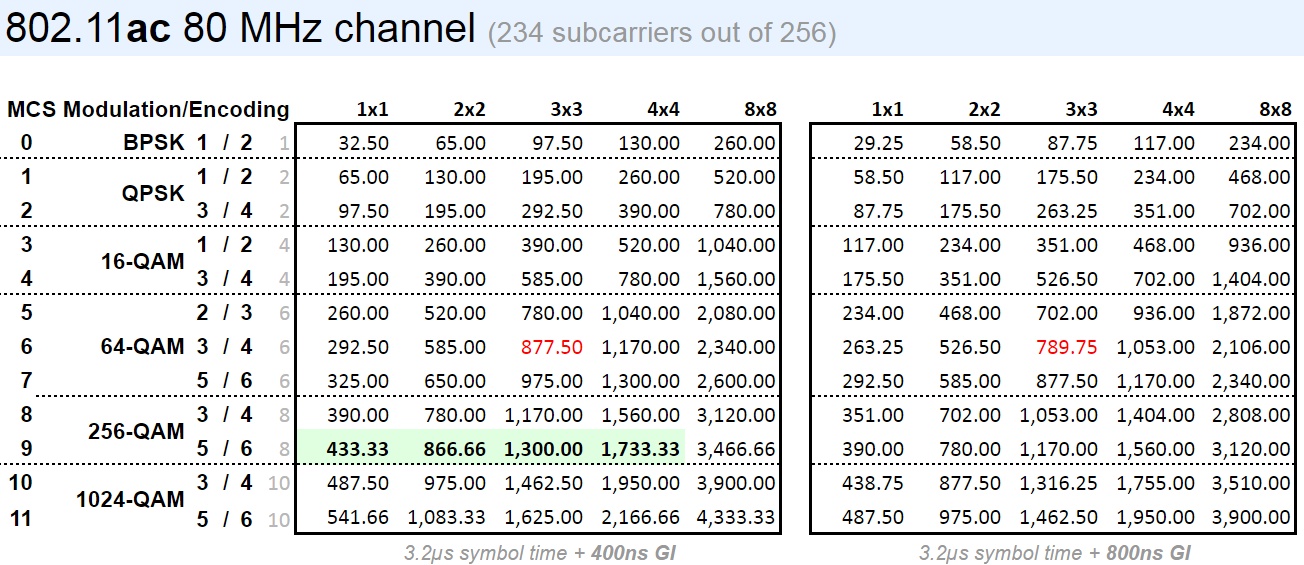

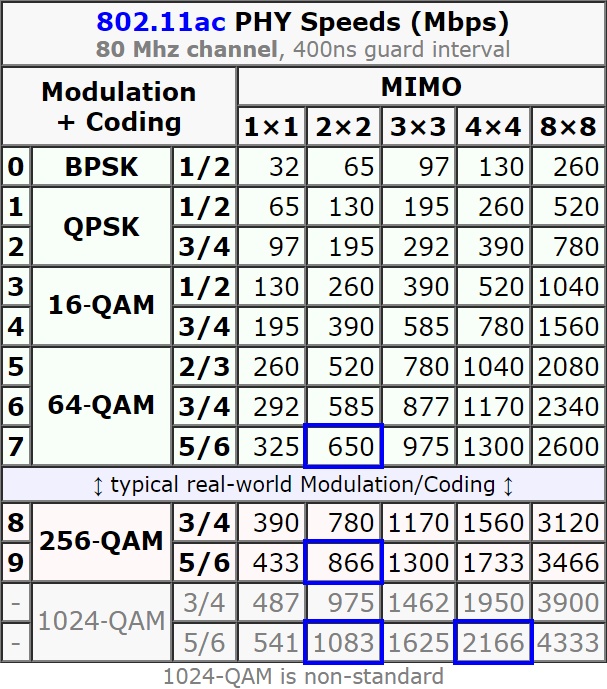

AC5300 rating: How did your router even get a 'rating' of 5300 Mbps in the first place? Router manufacturers combine/add the maximum physical network speeds for ALL wifi bands (usually 2 or 3 bands) in the router to produce a single aggregate (grossly inflated) Mbps number. But your client device only connects to ONE band (not all bands) on the router at once. So, '5300 Mbps' is all marketing hype. The following sections detail how the grossly speed of 5300 Mbps is reduced down to a 'real-world' speed of only 455 Mbps... 5300 → 2166: Maximum ONE band speed: The only thing that really matters to you is the maximum speed of a single 5 GHz band (using all MIMO antennas). You find out by looking at the 'tech specs' for an AP/router. 5300 is just 1000 + 2166 + 2166, where 1000 is the 2.4 GHz band speed and 2166 is the 5 GHz band speed. 2166 also is a tip-off that this router is a 4×4 MIMO router (by looking for '2166' in the speed table, right). More on bands in the Beware tri-band marketing hype section far below. 2166 → 2166: Realistic 80 MHz channel width: Router manufacturers cite speeds for 2.4 GHz using 40-MHz channel widths, but a 20-MHz channel width is much more realistic (that cuts cited speeds in half). For 5 GHz 802.11ac, speeds are typically cited for an 80-MHz channel width, which all AC clients are required to support. But if cited speeds are for a 160-MHz channel width (that is starting to happen for the new Wi-Fi 6 routers), cut the cited speeds in half (as most clients won't support that). 2166 → 1083: Client 2×2 MIMO: Which MIMO column do you use in the wifi speed table (right) -- The MIMO of the router or the MIMO of the client device? You must use the minimum MIMO common to both devices (often the client). So if you have a 4×4 router, but use a 2×2 client (like the Apple iPhone XS Max or Samsung Galaxy S8) to connect to it, maximum speeds will be instantly cut in half (2/4) from cited router speeds. Wi-Fi specifications for iPhone, iPad, or iPod. Virtually all newer iOS devices are 2×2 MIMO and older iOS devices are 1×1 (no MIMO). 1083 → 866: Client 256-QAM: You can only use the maximum (common) QAM supported by both the router and the client. Router manufacturers may cite speeds for 1024-QAM (which the router DOES support), but you will only get that if your clients supports that QAM (many do not) and you are very close to the router (sometimes only just feet away). So reduce to a much more realistic maximum of 256-QAM 5/6. 866 → 650: 32 feet from router (Modulation/Coding): Router manufacturers love to cite the maximum PHY speed possible, which you will only when you are very close (just feet) to the router. But as you move further away from the router, speeds gradually decrease. The 'distance' issue is represented by rows in the PHY speed table (seen upper right). At just 32 feet away from the router (a very typical distance), 64-QAM 5/6 was actually observed, so use that. For more details, see the next section. Analogy: Understanding Modulation/Coding: Imagine that once a second, you hold up your arms in various positions to convey a message to someone else. If you were only ten feet away from that person, the number of arm positions reliably detected would be very high. But now move 100 feet away. The number of arm positions reliably conveyed would be reduced. Now move 500 feet way. The number of arm positions reliably conveyed might be reduced to just 'did the arm move at all'. The same thing happens in wifi. If you are close to the AP/router, a large number of bits can be conveyed 'at once'. But as you move away, a smaller and smaller number of bits can be reliably conveyed 'at once'. So 'modulation/coding' is simply how much information can be conveyed at once, and is directly related to distance from the AP/router. 650 → 455: Wi-Fi overhead (MAC efficiency): What is the overhead at the network level? All of the speeds we have discussing so far are for PHY (physical) network speeds. But due to wifi protocol overhead, speeds at the application level are around 60% to 80% the physical network level. So use 70% as a fair estimate of throughput you can expect to see. 70% of 650 is 455 Mbps. Just Google 802.11ac MAC efficiency to understand this issue. In short, there are 'housekeeping' packets that MUST be sent at the SLOWEST possible modulation, and that takes time and slows everything down (along with other issues). 455 → ???: Interference/Contention: So, the final number is 455 Mbps for a 2×2 device (at a fair distance away from the router), but only if your device gets exclusive use of ALL time left in the wifi channel. But there may (or may not) be other wifi users (either local, or even neighbors on the same spectrum) which will decrease your speed by some unknown amount. Results: 2×2 MIMO devices get a realistic (maximum) download speed of 455 Mbps (±45 Mbps) at around 32 feet, which is dramatically lower than the '5300 Mbps' advertised by router manufacturers. A lesson learned: The two critical factors that greatly impact and determine maximum real-world speed for a single client are: (1) lowest common MIMO level support and (2) MAC efficiency.

YOUR client device is the key (limiting) factor for the speed (and maximum distance) at which your device connects to a router (a modern router is rarely the limit; for technical details, see prior section). Stay in this section for a fast shortcut. For a client device, expect 'top PHY speeds' (standing right next to the router) of:

With a new modern Wi-Fi 6 router, it is virtually never the router that has the speed limit, but rather, it is the client device (that is NOT as capable as the router) that limits speeds. For example:

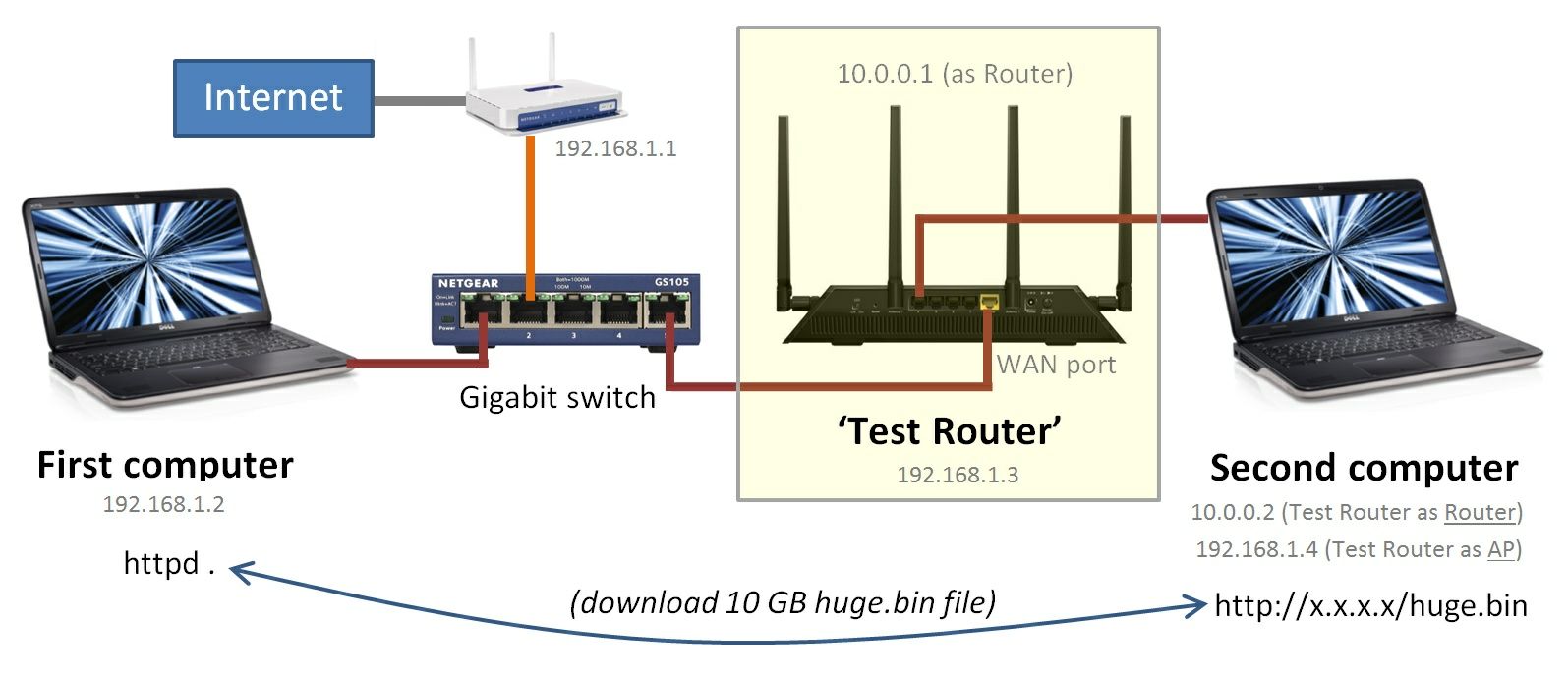

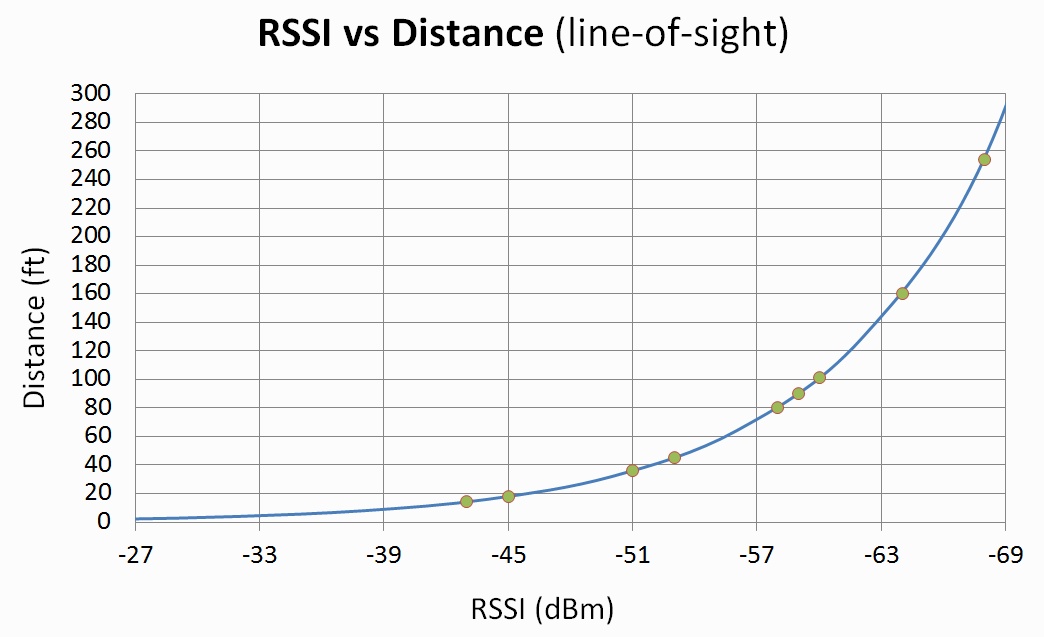

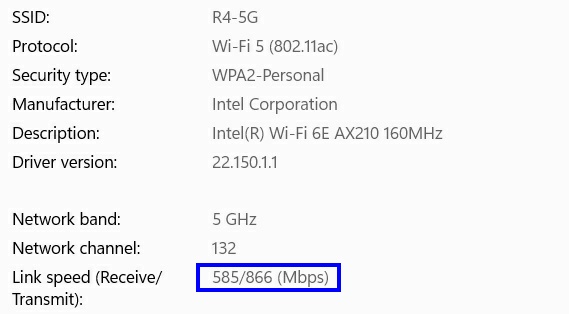

The problem (of finding maximum speed): So how do you find the maximum (realistic) wireless speed of a client to an AP/router? You could just run a speed test, but if the speed is not what you expected, where is the problem -- the client, the router, the Internet, interference, elsewhere, or is the speedtest accurate? The solution: Go to your wireless device and find the PHY speed (the raw bitrate between the device and your AP/router) and take 70% of that PHY speed to estimate maximum application speed (the next section explains why the overhead is so large). Then lookup the PHY speed number in the PHY speed tables to then find which MIMO level is currently being used.

Windows 11 (new way): Right-click on the Wi-Fi icon in the taskbar. Click on "Network and Internet Settings". Click on "Wi-Fi". Click on "XXX properties" (where XXX is the name of your Wi-Fi network). Scroll down to "Link speed (Receive/Transmit)". Windows 10 (new way): Go to the 'Settings' app, click on 'Networking & Internet', click on the 'View your network properties' link and find the transmit/receive speed under your 'Wi-Fi' adapter. However, I suspect that sometimes transmit/receive are just a single value displayed twice instead of two actual speeds.

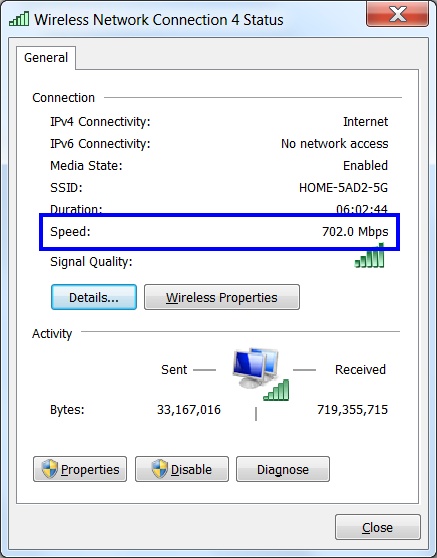

Windows 11/10/8/7 (legacy mode): In the Windows "Control Panel", search for and then click on "Network and Sharing Center", then click on the named wireless connection (which opens a 'status' dialog), and look for the 'Speed' (example seen right). Example: Lookup 702 Mbps speed (right) in the PHY tables far below and it is not found. So, go to the full PHY speed tables and you will find various matches, but only one makes logical sense: 80 MHz channel, 2×2 MIMO, 256-QAM. Mac: (1) Hold the option/alt key down and click the Wi-Fi icon in the menu bar and look for the "Tx Rate". (2) Run the "Network Utility" (under Applications / Utilities; or use Spotlight to find) and look for the wifi "Link Speed". [ iOS (iPhone/iPad/iPod): Not known (tell me if you know how). However, to find the maximum PHY speed and MIMO level for your iOS device, visit the Wi-Fi specification details for iPhone, iPad, or iPod. All modern iOS devices are 2×2 MIMO. UPDATE: Here is a tip I received -- if you happen to use Apple's AirPort WiFi base station: "Install Apple's 'airport utility' and then open it. Click on the wifi base station. Click on 'wireless clients' and then click on your iOS device and then 'connection'. This will give you the iOS device 'PHY' connection speed."

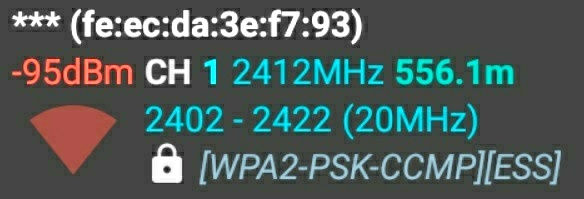

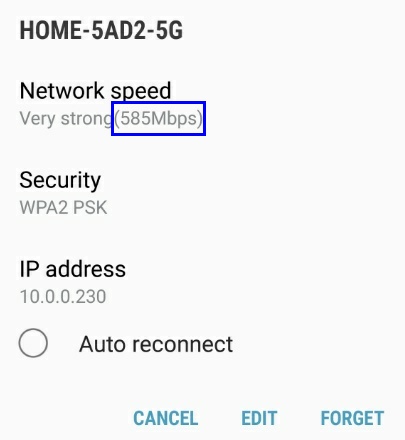

Android: Go into "Settings / Connections / Wi-Fi", click on the connected wifi network, and find the 'Network Speed' (example right). Or, it may also be called 'Link Speed'. Example: Lookup 585 Mbps (right) in the PHY tables far below, and you will find it in multiple columns, but given the client, what makes the most sense is: 80 MHz channel width, 2×2 MIMO, and 64-QAM. Kindle: Under Settings, click on "Wireless", then click on the connected wifi network, and look for "Link speed". Chromebook: Open "crosh" on your Chromebook (CTRL-ALT-T) and type "connectivity show devices" and look for the Link Statistics Transmit Bitrate. You should see: (1) the Mbps transmit bitrate, (2) the MCS index number, (3) the channel width in MHz, and (4) the number of spatial streams. Type "exit" to exit/close the crosh window. Netgear Router TIP: In the Netgear 'Nighthawk' router app, click on 'Device Manager', then click on a client device, and a "Link Rate" will be displayed. But Netgear displays a 'link rate' that is slightly too small. To correct (to bps), multiply by 1024/1000 (thanks to Matthew S. for pointing that out). Comcast Gateway TIP: If you use a Comcast provided cable modem / gateway device, connecting to the http administration interface, signing in, and clicking on the 'View Connected Devices' button will take you to a page that shows the "RSSI Level" (in dBm) for all Wi-Fi connected devices. Very helpful!

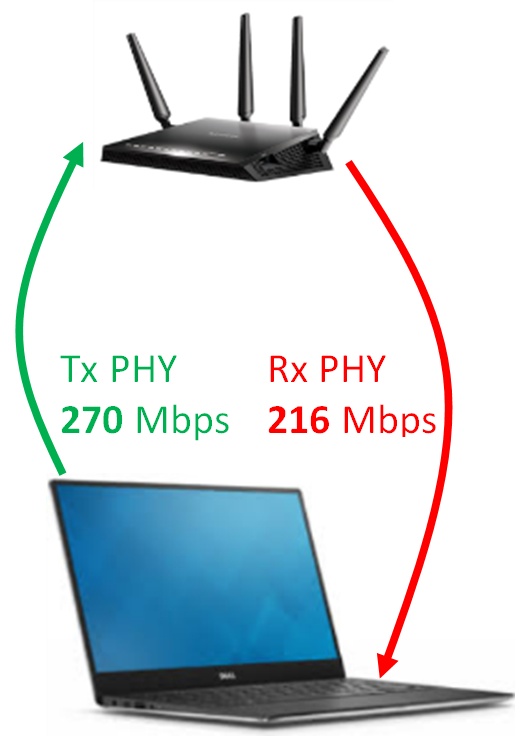

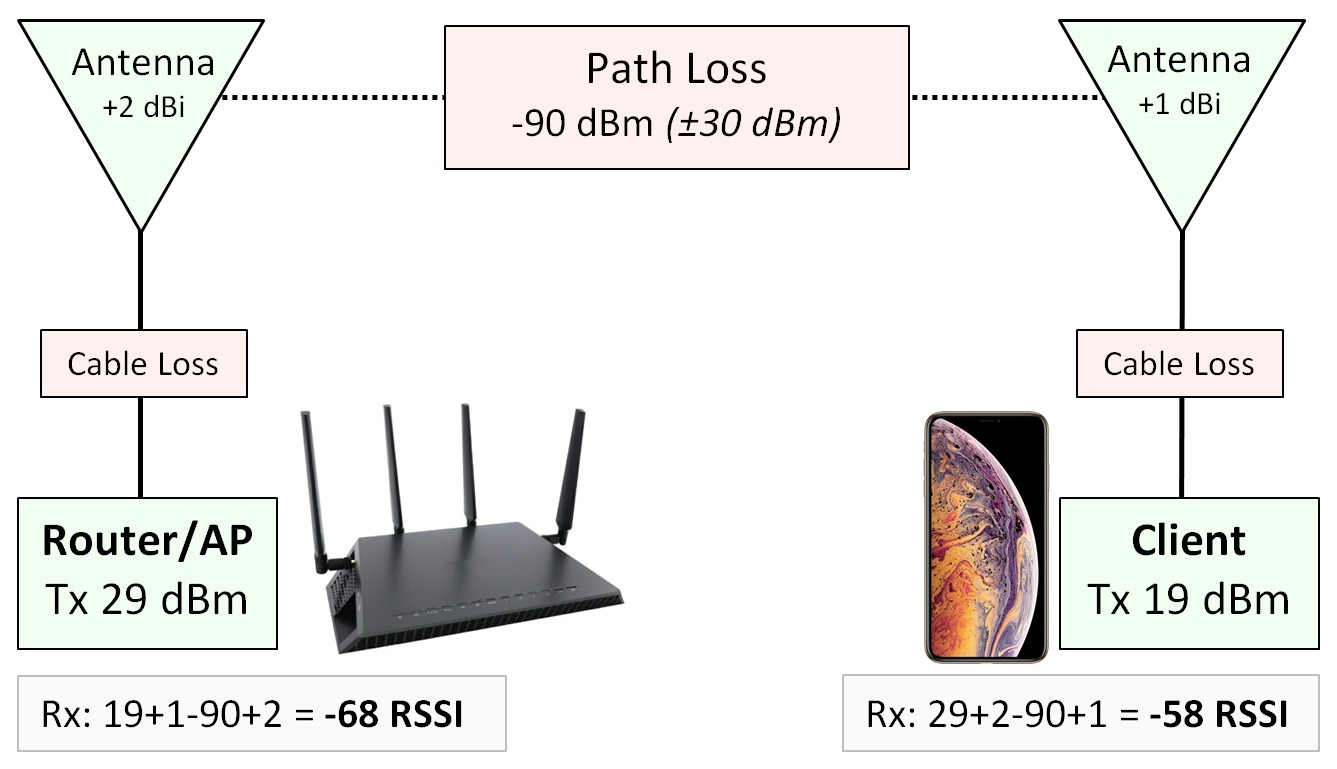

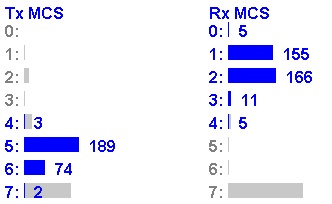

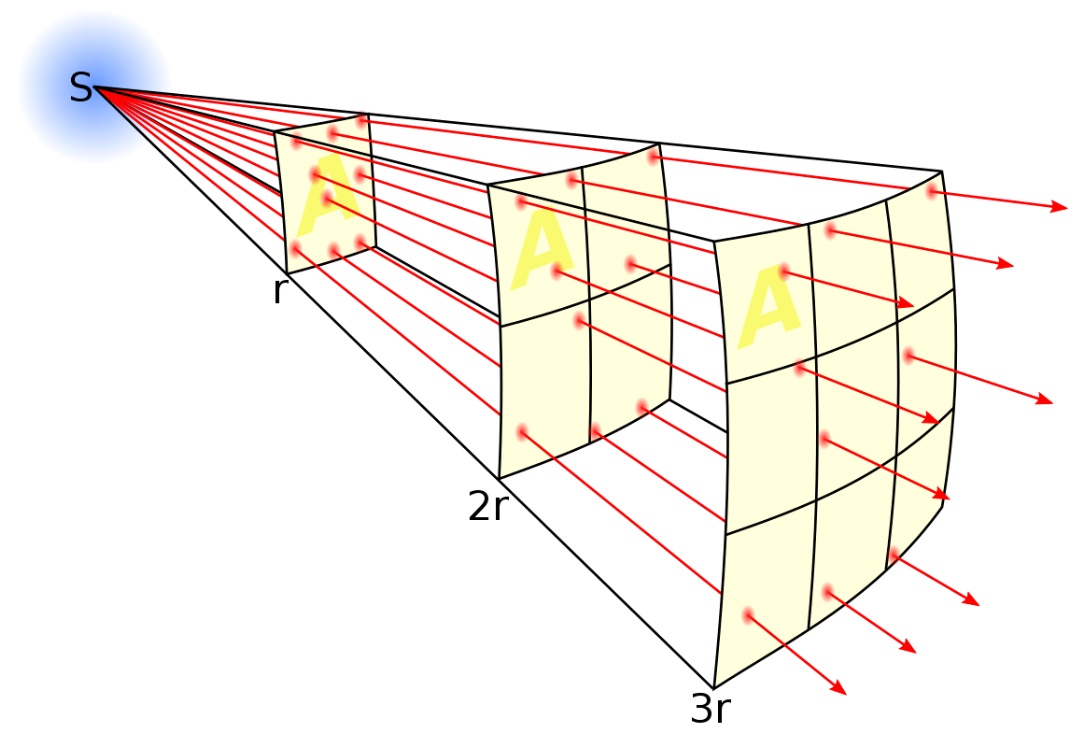

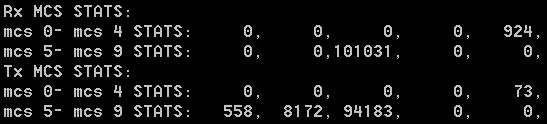

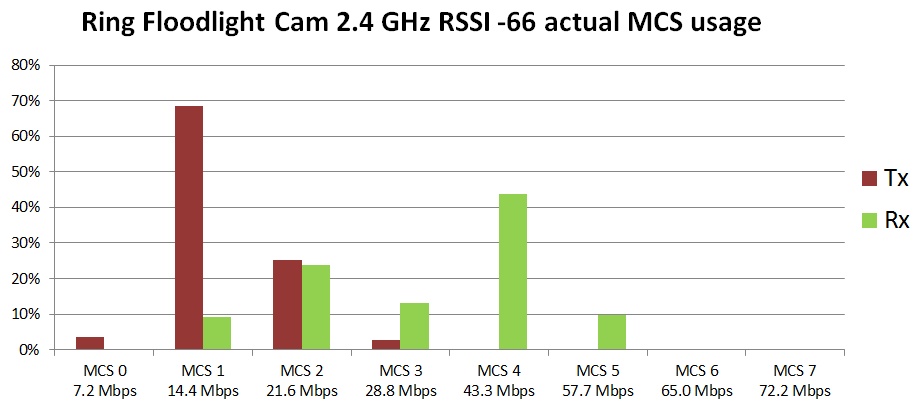

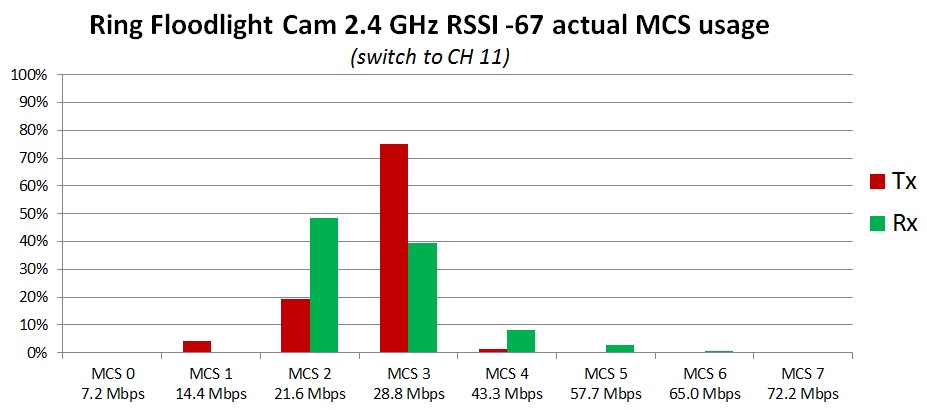

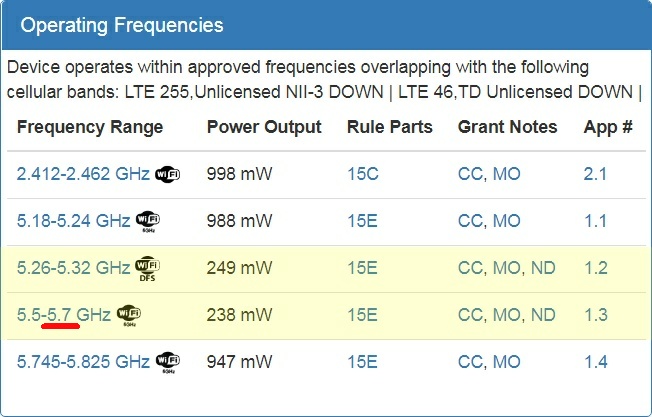

MOST client devices today are stuck at 2×2 MIMO: As can be seen from the tables (right), most client devices today are STILL only 2×2 MIMO. Why haven't devices switched to 4×4? Because (1) there is (currently) no compelling need for that speed today (there is no app that 'requires' 400 Mbps to function) and more importantly (2) the increased speed is not worth the tradeoff in greatly reduced run time for battery powered devices. Supporting 4×4 MIMO takes a lot more power, and for battery powered devices, runtime is FAR more important. You can expect a maximum PHY speed of 866 Mbps, and around 600 Mbps (±60 Mbps) throughput, from a Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) 2×2 client device. It is noteworthy to point out that Dell apparently had a 3×3 laptop in the past, but Dell only offers a maximum 2×2 laptop as of February 2019. A final warning: This discussion about 'the' PHY speed of your device is slightly over simplified, as for every wifi device, there is actually a Tx (transmit) PHY speed and a Rx (receive) PHY speed, and those two speeds are almost always different (asymmetric). But even when different, the two speeds are relatively close to each other, so the asymmetry is rarely noticed. See the PHY speed is asymmetric appendix below for more details. A final wrench in the PHY puzzle: And PHY speed is not 'constant'. Unless you are right next to the router (with a fantastic signal strength and PHY speed is highest possible speed), PHY speed is actually constantly changing up and down between MCS levels, adapting to changing signal strength conditions. It is not uncommon with a single second to see 3 to 4 different MCS levels (PHY speeds) used. Are you highly technical? Then use the Router deep dive appendix below to determine exactly what MCS indexes are being used for both Tx PHY and Rx PHY. Another client device limitation: Range: The maximum distance at which a device can connect to an AP/router is (almost always) determined NOT by the power output of the AP/router (around 950 mW is typical), but the power output of the client device (around 50 mW to 250 mW typical), as client devices almost always operate at lower power levels than the AP/router. The implication of this is that the Tx PHY speed from a client device to an AP/router is almost always lower (hits the limit sooner) than the Tx PHY speed from the AP/router to the client. Full details.

The bottom line: Under ideal conditions, you can and should expect Mbps throughput around 70% (±10%) of the client PHY Mbps speed. But in many situations (for tons of various reasons), overhead and contention can cause throughput as low as 50% of PHY speed. KEY Wi-Fi concept: Expect Wi-Fi throughput to be around 70% (±10%) of PHY speed.

Wifi overhead can be surprisingly 'large': So, if your smartphone connects to your AP/router at a PHY speed of 702 Mbps, why doesn't your smartphone get that full speed? Instead, 70% of your PHY speed (70%×702=491 Mbps) is a fair estimate of actual (maximum) Mbps seen, but why? PHY speed in wifi is exactly like the speed limit (sign) on a local road. You can go that fast some of the time but clearly not all the time. Because you must take into account known slow downs: stop signs, turns, traffic lights, traffic, school zones, weather conditions, etc. And in Wi-Fi, there are a lot of slow downs that add up.

First, there is TCP/IP and Ethernet overhead: On wired Ethernet, you can expect around 5% overhead for TCP/IP and Ethernet, or 95% throughput at the application level. As a ballpark figure, assume something very similar for wifi. Just remember that part (around 5%) of the total overhead you are seeing in Wi-Fi is actually coming from TCP/IP and Ethernet protocol overhead, and not Wi-Fi itself. Management transmissions must be sent at the 'slowest' possible modulation: In order to guarantee that ALL devices on a channel (AP and clients) can receive+decode management transmissions, those transmissions must be transmitted at the slowest possible modulation -- so that devices that are furthest away from the AP (and hence, running at the slowest speed) can receive and successfully decode those transmissions. For example, 802.11 'Beacon Frames' (typical send rate is once every 102.4 ms). And this 'slow' speed can be as slow as 1 Mbps (2.4 GHz band) or 6 Mbps (5 GHz band). When compared to 433 Mbps and 866 Mbps, that 'slow' speed is a hit. SSID overhead: The overhead per SSID (on one channel) can be anywhere from 3% to incredibly high. Half Duplex: There is no separate download spectrum and upload spectrum in wifi (whereas Ethernet is full duplex - can send and receive at the same time). Instead, there is only a common spectrum (channel) that ALL wifi devices (router and clients) operating on that channel must use in order to transmit (and receive!). So when you are running that download throughput speed test, your device is mostly receiving, but it is also transmitting (acknowledging data sent)! Using the MCS Spy tool , a PC downloaded at 120 Mbps, but was uploading at 1.8 Mbps at the same time. This is simply due to how TCP/IP works. And almost always, the client transmits back to the AP at a slower MCS than the MCS the router uses to transmit to the client. So because wifi is half duplex, there may be around 1% to 3% (relative) 'overhead' simply due to how TCP/IP works (acknowledgements). CSMA/CA: The Wi-Fi spectrum is a shared resource. So how does a device know that it is OK to transmit? Wifi uses something called CSMA/CA (Carrier-Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance). So any device on a channel that wants to transmit must first 'sense' that the spectrum is available/unused. And to ensure 'fairness' to all wifi stations that want to transmit, all 'want to transmit' stations wait a random amount of time before transmitting (if the spectrum is still unused at that point, and hope for no collisions). And if you have a lot to transmit, that 'wait for a random amount of time' over and over adds up. But that random wait is necessary to ensure 'fairness' to other wifi devices. Acknowledgements: Every Wi-Fi packet sent must be 'acknowledged' (to confirm receipt). To accomplish this, each sent packet has a little bit of an extra reserved space (a 'time window') appended to the end of the packet, for the receiver to transmit back (during the empty 'time window') an 'I got it' acknowledgement (to the sender). Collisions/Retransmissions: When multiple devices want to transmit at once (as the channel gets busy), the possibility of collisions (more than one device transmitting at the same time) increases, causing that entire transmission to be lost, and a future retransmission. Or a transmitted packet just did not make it. From a test AP, there were 1,519,932 packets transmitted and 48,878 packets retransmitted. So, around 3% of the data packets had to be retransmitted.

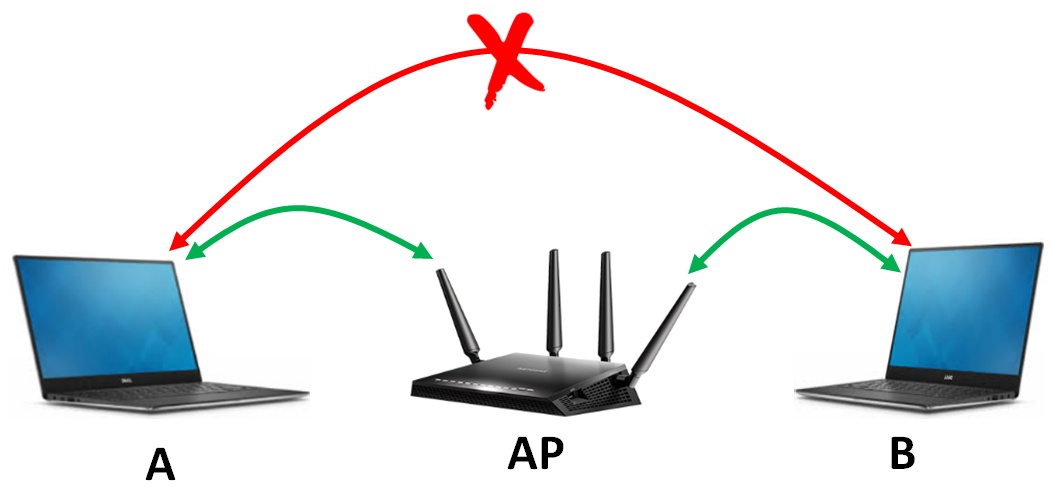

Hidden Node Issue: There is something called the Hidden Node Problem that can (potentially) cause a large number of collisions in wifi -- where device 'A' and device 'B' can both hear transmissions from the AP, but device 'A' and device 'B' can NOT hear each other's transmissions. So both device 'A' and device 'B' might transmit at the same time (as seen at the AP, a 'collision') and both transmissions are lost (at the AP). A mitigating factor is that even if your network has the hidden node problem, the hidden nodes will not impact each other, unless they attempt to use wifi and transmit at the exact same time. If both hidden nodes are sporadically using wifi, the problem will not happen that often. Coexistence with 802.11 a/b/g/n: For an 80 MHz 802.11ac channel to properly coexist with older 20 MHz radios operating within the channel, there is a 'request to send' and 'clear to send' exchange before each real message is sent. And that slows everything down. Beamforming overhead: The sounding frames for beamforming adds a tiny bit of overhead. How much overhead this causes needs to be researched. CRITICAL: Don't forget that Wi-Fi is a shared resource: After all of the above (which assumes you have the Wi-Fi channel all to yourself), if you are unlucky enough to have a router set to the same channel as your neighbor (and your neighbor is using Wi-Fi), you are sharing spectrum/time/bandwidth with your neighbor! How is Wi-Fi spectrum shared? By bandwidth? By time? By something else? In general, by TIME -- if 'N' users all want to use Wi-Fi at the same time, on average, they will all get to use the channel '1/N' of the time. For example, if two users want to use the same channel, and first user at a PHY of 6 Mbps, and the second user at a PHY of 866 Mbps, the first user will get to use the channel 50% of the time (so 6/2, or around 3 Mbps), and the second user will get to use the channel the other 50% of the time (so 866/2, or around 433 Mbps). A final caveat: PHY speed is a very complicated thing. Tx PHY and Rx PHY can not only be asymmetric (more details below), but also be highly variable. The 'link speed' your device reports to you is a highly over-simplified single number. You should only use that speed as a 'ballpark' figure of actual PHY speeds used. Or, when you run a throughput test and attempt to calculate the 'overhead' at the PHY level, that 'overhead' is only an estimate. A prime example: A Windows laptop with an 'older' 802.11ac 2×2 MIMO four feet from the router reports (an expected) 'speed' of 866.6 Mbps (MCS9). A throughput tests shows download speeds of 475 Mbps. That is a MAC efficiency around 55%. But the MCS Spy tool (see Router deep dive appendix below) clearly shows that the router is transmitting to the PC using only MCS7 (650 Mbps), which is actually a much better MAC efficiency of around 75%. There is still the problem of why MCS9 is not being used, but MAC efficiency is much better than it initially appears. Learn More:

The bottom line: The AC#### naming convention (AC1900, AC2600, AC5300, AC7200) and AX#### naming convention (AX6000, AX11000) used in the router industry (where the #### is a maximum combined Mbps) is nothing more than marketing hype/madness. The naming convention implies (incorrectly) that the larger the number, the better and faster the router -- and the faster wifi will be for your wireless devices. Also, speeds are cited for hypothetical wireless devices that DO NOT EXIST -- can you actually name a single smartphone, tablet, or laptop computer that has 4×4 MIMO for Wi-Fi? KEY Wi-Fi concept: There is a lot of marketing hype in the claims made by router companies.

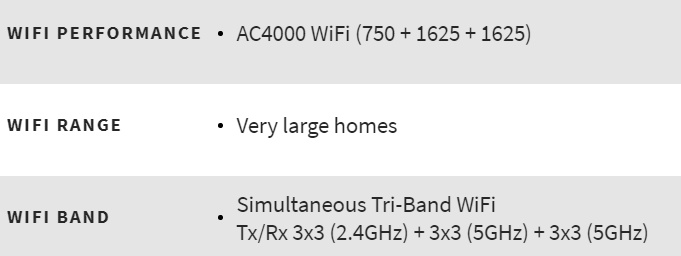

Example: Seen upper right are the specifications for an AC4000 (4000 Mbps) class router. But realistically, what speed can YOU expect from your "iPhone XS Max", a 2×2 MIMO device, at a reasonable distance of 32 feet? Bands/MIMO: AC4000 is 750+1625+1625. So what do those numbers mean? It is the 'maximum' speeds (best modulation possible with highest MIMO) of all 'bands' in the router added together as follows:

MAC Overhead: Take the 5GHz PHY speed (for one 5 GHz band, not both bands, so 650) and multiple by 70% to get an estimate of the Mbps speeds that you will see within speed test applications running on your wireless device. Conclusion: At 32 feet, you will get a maximum speed of around 455 Mbps (±45 Mbps) from your iPhone XS Max from this '4000 Mbps' router. With a second AC band, you 'might' get up to 455 Mbps from another wireless device at the same time (but see tri-band router section below). So upgrading to a faster router will increase your iPhone XS Max speeds, right? No! What about an AC5400 4×4 tri-band router? Same speed. What about a brand new ultra-fast Wi-Fi 6 AX6000 8×8 router, marketed as being 4x faster than Wi-Fi 5? Same speed. Understand router manufacturers' marketing hype.

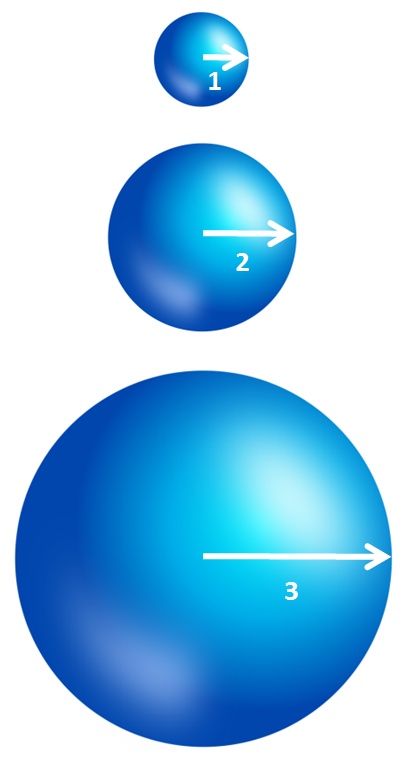

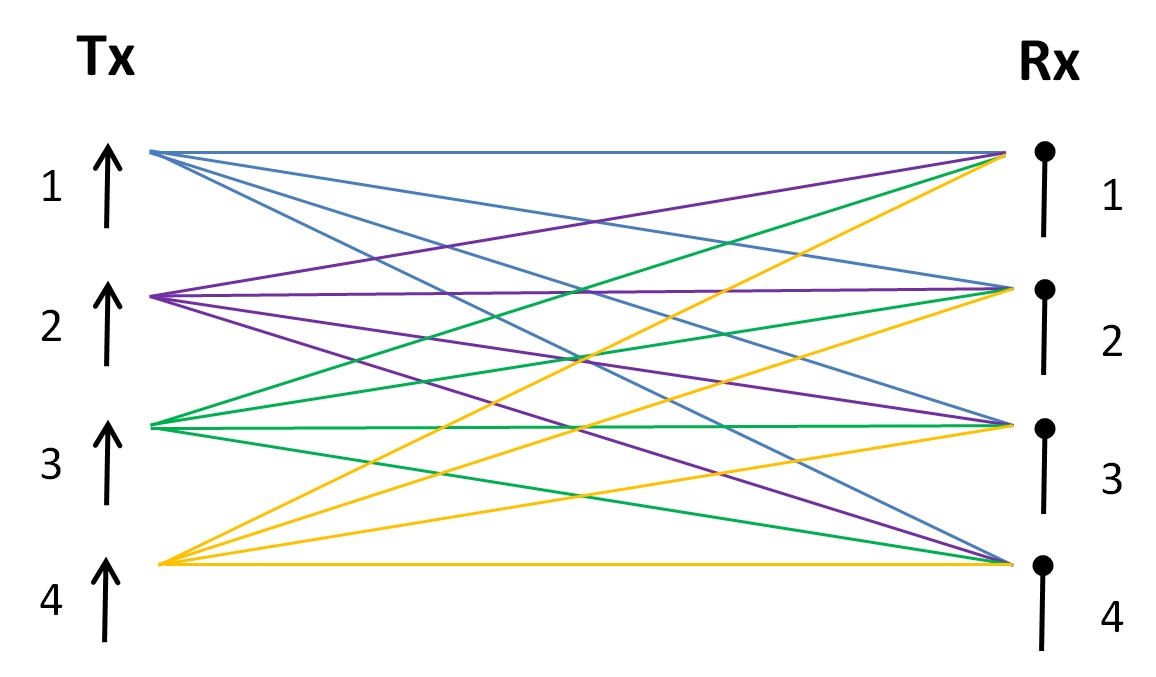

MIMO: What is (partly) driving the dramatic increase in wireless (wifi, cellular, etc) capacity in the last few years is MIMO (acronym for Multiple Input, Multiple Output), or spatial multiplexing, or spatial streams -- by using multiple antennas all operating on the same frequency at the same time. Most smartphones today are capable of 4×4 cellular MIMO -- so they are (potentially) four times as fast as a single antenna phone. But MIMO for wifi is stuck at 2×2 MIMO for most wireless wifi (client) devices. Analogy: Think of MIMO as adding 'decks' to a multi-lane highway. More lanes (capacity) are added without using more land (spectrum). 2×2 MIMO is a highway with one more highway deck above it. And 4×4 MIMO is a highway with three more highway decks above it. What is the big deal: The reason MIMO is such a huge deal is because it is a direct capacity multiplier (×2, ×3, ×4, ×8, etc) while using the SAME (no more) spectrum. This is accomplished by simply using more antennas (by both the router and client). MIMO adds more capacity without using more spectrum! Example: On a single 80 MHz 802.11ac channel operating at 433 Mbps:

all on the same 80 MHz channel. Notation: You might see the MIMO level written as T×R:S, where 'T' is the number of transmit antennas, 'R' is the number of receive antennas, and 'S' (an optional component) is the number of simultaneous 'streams' supported. If the 'S' component is missing, it is assumed to be the minimum of 'T' and 'R'. OR, some devices will just say '2 streams' (for 2×2:2) or 'quad stream' (for 4×4:4). Diversity: Multiple antennas can also be used to improve link quality, and increase range. With multiple antennas receiving the same transmitted signal, the receiver can recombine all of the received signals into a better estimate of the true transmitted signal. FCC documents discuss that the 'maximum' gain when doubling antennas is 10×log(NANT/NSS) dBi, which for a 2×2 client to a 4×4 access point, would result in a diversity gain of 'around' 3 dBi.

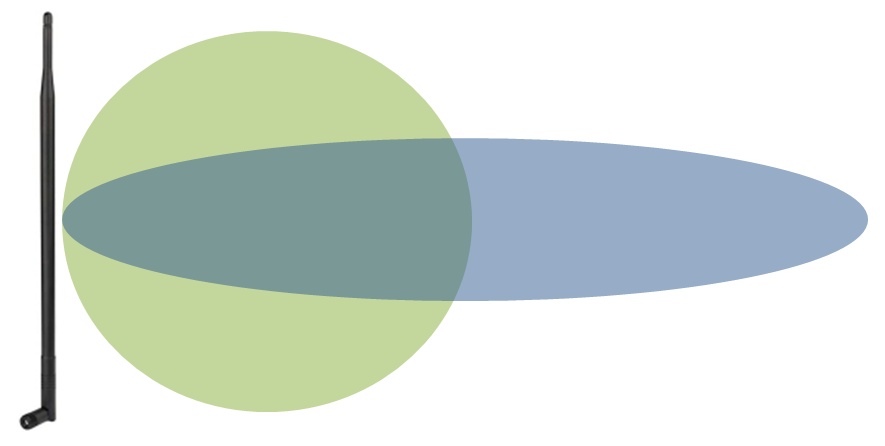

Beamforming: This Wi-Fi technology uses multiple antennas to 'focus' the transmitted RF signals more towards a device (instead of just broadcasting the signal equally in all directions). The end result is a slightly stronger signal (in the direction of the device), which typically causes a slightly higher modulation to be used, which in turn increases Mbps speed by a little bit. KEY Wi-Fi concept: It is easy to overlook and miss, but beamforming and diversity are the key reasons why you want a 4×4 MIMO router even though most clients are still only 2×2 MIMO. The extra antennas are actually used and offer significant value (a stronger signal, which translate to better connect speeds for far-away users)! Client MIMO: Almost all battery powered wireless devices are stuck at 2×2 MIMO for wifi, and this seems unlikely to change anytime soon. The extra power requirements of 4×4 MIMO causing reduced run times is just not worth the tradeoff (yet). But for devices with lots of power (like a PC on AC power), you can buy 4×4 MIMO adapters. Must a client device with MIMO always use MIMO? No, it does not have to. I have a Dell laptop with an "Intel Wi-Fi 6E AX210" card that I have documented flipping back and forth between 1×1 and 2×2 data rates (keeping the MCS level the same) depending upon conditions. This needs more research (is this a bug or a feature). A final note: You will only get the dramatic speed benefits of MIMO if you have a client device (phone, tablet, TV, computer, etc) that actually supports MIMO. Most client devices today (April 2023) are STILL (at best) 2×2 MIMO. It is very rare to see a (battery powered) client device that supports 3×3 (or higher) MIMO.

Learn More:

Reference: A brief look at past legacy wifi generations (and while not official names, Wi-Fi 1, Wi-Fi 2, and Wi-Fi 3):

802.11 (Wi-Fi 1): PHY data rates of 1 or 2 Mbps using direct sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) with three non-overlapping 22 MHz channels in 2.4 GHz (1, 6, 11). 802.11b (Wi-Fi 2): PHY data rates of 1, 2, 5.5, or 11 Mbps using direct sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) with three non-overlapping 22 MHz channels in 2.4 GHz (1, 6, 11).

802.11a (Wi-Fi 3): PHY data rates 6 Mbps to 54 Mbps (see table right) using orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) with 12 non-overlapping 20 MHz channels in 5 GHz (36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 56, 60, 64, 149, 153, 157, 161), but some channels (52-64) had DFS restrictions. . But 802.11a really never 'took off' since initial 802.11a devices worked only in the 5 GHz band (did NOT support existing 802.11b clients in the 2.4 GHz band) and were expensive (as compared to 802.11b products). The router industry learned a hard lesson -- that any new router/AP must also be backward compatible (must support most, if not all, of the old client devices out there)! New routers today support ALL prior generations of Wi-Fi back to 802.11b. 802.11g (Wi-Fi 3): Wi-Fi 3 802.11a technology in 5 GHz was moved/extended back into the 2.4 GHz band. PHY data rates 6 Mbps to 54 Mbps (see table right) using orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) with three non-overlapping 20 MHz channels in 2.4 GHz (1, 6, 11) -- see the next section for details. Wi-Fi 3 also could revert to 802.11b mode to support older clients -- so 802.11g was highly successful. And it worked incredibly well considering that typical residential broadband Internet speeds back then were around 3 Mbps. It is remarkable that today you can still today buy a brand new Linksys WRT54GL router (802.11g). ★ The big advance in Wi-Fi 3 was the introduction of OFDM, instantly improving throughput nearly five times over the prior Wi-Fi 2 (from 11 Mbps to 54 Mbps; only for AP/clients that support OFDM). Learn More:

★ The big advance in Wi-Fi 4 was the introduction of MIMO (multiple antennas), instantly doubling (for 2 antennas) or tripling (for 3 antennas) throughput over the prior Wi-Fi 3 (but both client/AP must implement MIMO).

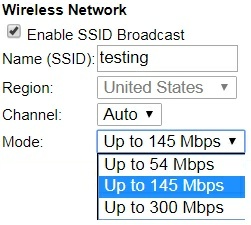

217 Mbps speed: The 217 Mbps maximum PHY speed is for a 20 MHz channel to a 3×3 MIMO client. However, a much more realistic maximum PHY speed is 144 Mbps for a 20 MHz channel to a 2×2 client.

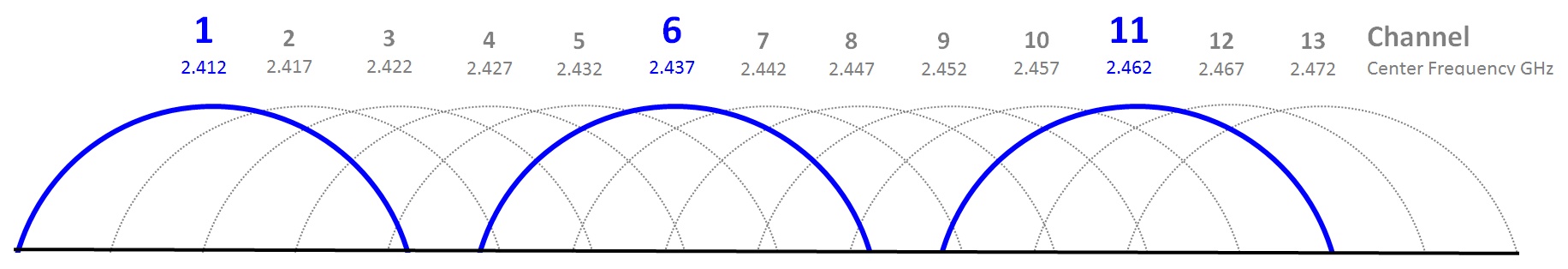

Spectrum: There is ONLY 70 MHz of spectrum (2402-2472 MHz) available for wifi to use in the U.S. in the 2.4 GHz band, supporting only three non-overlapping 20MHz channels. There are eleven OVERLAPPING 2.4 GHz wifi channels: In the US, wifi routers allow you to set the 2.4 GHz wifi channel anywhere from 1 to 11 (wiki info). So there are 11 wifi channels, right? NO! These eleven channels are only 5MHz apart -- and it actually takes a contiguous 20MHz (and a little buffer MHz between channels) to make one 20MHz wifi channel that can actually be used. Because of this, in the US, these restrictions result in only three usable non-overlapping 20MHz wifi channels available for use (1, 6, or 11; seen right). The THREE non-overlapping channels: You CAN set to the wifi channel to any channel and it will work. However, if you don't select 1, 6, or 11, the 20 MHz channel you create will almost certainly impact TWO other 20 MHz (neighbor) channels operating on 1, 6, 11. And more importantly, the TWO neighbor channels will impact your one channel. Not good. If your AP/router uses channel 2, 3, 4, 5, or 7, 8, 9, 10, that is an error to fix! So be a nice neighbor and only use one of the three non-overlapping channels: 1, 6, or 11!

A small gap between channels: Notice the very small 5 MHz gap between channels 1, 6, and 11. This is very intentional and designed so that (hopefully) traffic on one channel does not interfere with traffic on an adjacent channel. Shared spectrum: All wifi devices on the same spectrum must SHARE that spectrum. Ideally, all wifi devices decide to operate on either channel 1, 6, or 11 -- the only non-overlapping channels. Then all devices operating on a channel share that channel. But I have seen routers operate on channel 8, which means that router is being a 'bad neighbor' and interfering with 20 MHz channels operating on 6 and 11. Protocol Overhead: Each 20MHz wifi channel has PHY bitrate of around 72Mbps, but due to wifi protocol overhead, you may only get to use around 60% to 80% of that. In a very 'clean' wifi environment, I have seen throughput around 54.2 Mbps for a PHY speed of 72.2 Mbps, which comes out to 75% efficiency -- pretty good. Another time, when I was just feet from the router, I measured a peak throughput of around 118 Mbps for a PHY speed of 144.4 Mbps (82% efficiency) -- very good.

Understanding channel widths: The standard wifi channel width is 20 MHz. So a 40 MHz channel is TWO 20 MHz channels put together (2× capacity). Analogy: Think of channel width as how many 'lanes' you can use at once on a multi-lane highway. 20 MHz is a car using a single lane. 40 MHz is a 'wide' load trailer using two highway lanes. Channel bonding / 40MHz channels: This is the biggest marketing rip-off ever (in 2.4 GHz). Routers can then advertise 2x higher speeds, even though in virtually all circumstances, you will only get 1/2 of the advertised speed (only be able to use a 20 MHz channel)! For example, The Netgear N150 (implying 150Mbps), which is the result of taking TWO 20MHz wifi channels and combining them into one larger 40MHz channel, doubling the bitrate. This actually does work, and works well BUT ONLY in 'clean room' testing environments (with NO other wifi signals). However, for wifi certification, the required 'good neighbor' implementation policy prevents these wider channels from being used in the real world when essentially the secondary channel would interfere with neighbors' wifi -- which unless you live in outer Siberia, you WILL 'see' neighbors' wifi signals and the router will be required to automatically disable channel bonding. I am curious if this issue had anything to do with why Netgear stopped getting their routers 'Wi-Fi Certified'? 256-QAM and 1024-QAM HYPE: These are non-standard extensions to 802.11n, so most client devices will never be able to get these speeds. And even if you have a device that is capable of these speeds, are you close enough to the router to get these speeds? Understand that advertised speeds in these ranges are mostly marketing hype. See Broadcom TurboQAM and NitroQAM. The reason why 256-QAM and 1024-QAM are included in the PHY tables here is for reference/convenience -- because these PHY tables ARE ALSO the PHY speed tables for 802.11ac for 20 MHz and 40 MHz channel widths. The PHY speeds for an 80 MHz channel is far below in the next section. Interference: The entire 2.4 GHz space is plagued by interference (a victim of the success of the 2.4 GHz band), or other devices using the SAME frequency range. For example, cordless phones, baby monitors, Bluetooth, microwave ovens, etc. Microwave ovens operate at 2450 MHz ± 50 MHz. (source), which is the entire wifi space, and very likely impacting two of the wifi channels, and in some cases, even all three wifi channels Microwave ovens are licensed in the entire ISM (Industrial, Scientific and Medical) band from 2.4 GHz to 2.5 GHz, which covers all 2.4 GHz wifi channels. Proprietary beamforming: Some 802.11n devices did support 'beamforming', but these were proprietary extensions that required matching routers and clients (one vendor's implementation would not interoperate with a second vendor's implementation). The BOTTOM LINE: The 2.4 GHz band is just WAY too crowed. It is a victim of its own success. Use a modern dual-band (2.4 and 5 GHz) router/AP and switch over to the 5 GHz band -- for all devices that support 5 GHz. All quality devices made in the last few years (phones, tablets, laptop computers, TVs, etc) will absolutely support 5 GHz for Wi-Fi. In a resort community, with homes very close to each other, a Wi-Fi analyzer app shows well over 15 2.4 GHz networks within range. At night, Wi-Fi performance (actual throughput) on the 2.4 GHz band was horrible due to contention (sharing bandwidth) with many neighbors. However, performance on the 5 GHz band was excellent. A final warning: I am glossing over the fact that 802.11n can also operate in the 5 GHz band, using 20 MHz and 40 MHz channels (but not 80 MHz channels and not 256-QAM), because 802.11ac is so common place today. Just be aware that 802.11n using 5 GHz is possible using 'dual-band 802.11n' wifi devices -- don't assume a wifi device operating in 5 GHz is 802.11ac (it may only be 802.11n). There are still brand new dual-band 802.11n routers and devices (smartphones, doorbell cameras, etc) being sold today that are 802.11n dual-band (and not 802.11ac)! Understanding where the speed increases in 802.11n (over 802.11g) came from: 54 Mbps in 802.11g becomes 58.5 Mbps in 802.11n by using 52 subcarriers out of 64 (instead of just 48), which then becomes 65 Mbps by reducing the guard interval (GI) from 800ns to 400ns, which then becomes 72.2 Mbps via a new QAM modulation, which then becomes 144 Mbps and 217 Mbps via MIMO. So MIMO is the key factor for dramatically increased speeds in 802.11n over 802.11g. So why is 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi 4 not considered 'legacy' Wi-Fi: Frankly, it is and should be considered legacy (and not used much anymore)! But the surprising fact is that many brand-new IOT devices (especially 'battery' devices) being sold today only come with 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi 4 support.

★ The big advance in Wi-Fi 5 was moving into the 5 GHz band and the introduction of 80 MHz channels, instantly quadrupling throughput over the prior Wi-Fi 4 with 20 MHz channels (but both client/AP must implement 80 MHz channels).

The fifth generation of wifi is 802.11ac (2013) on 5 GHz. It provides a maximum PHY speed of 3.4 Gbps on an 80 MHz channel using 8×8 MIMO (and fully backward compatible with prior wifi generations). However, a much more realistic maximum PHY speed is 1.7 Gbps on an 80 MHz channel using 4×4 MIMO. Wi-Fi 5 has now been 'officially' replaced by 802.11ax Wi-Fi 6 (see next section).

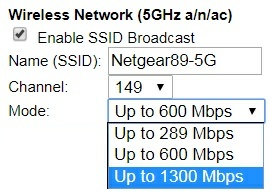

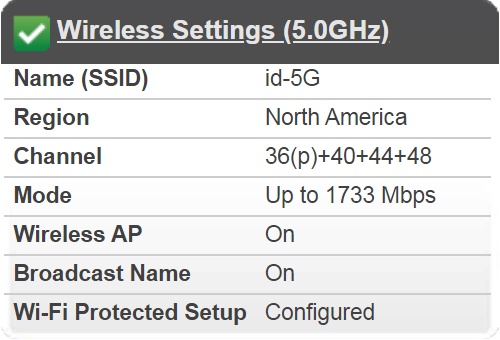

1733 Mbps speed: The 1733 Mbps maximum PHY speed is for an 80 MHz channel to an 4×4 client. You can find 4×4 wifi cards for your PC. However, a much more realistic maximum PHY speed (for 'on battery' devices) is 866 Mbps for an 80 MHz channel to a 2×2 client, and in the real-world, a PHY speed of 780 Mbps is reasonable.

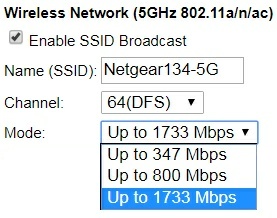

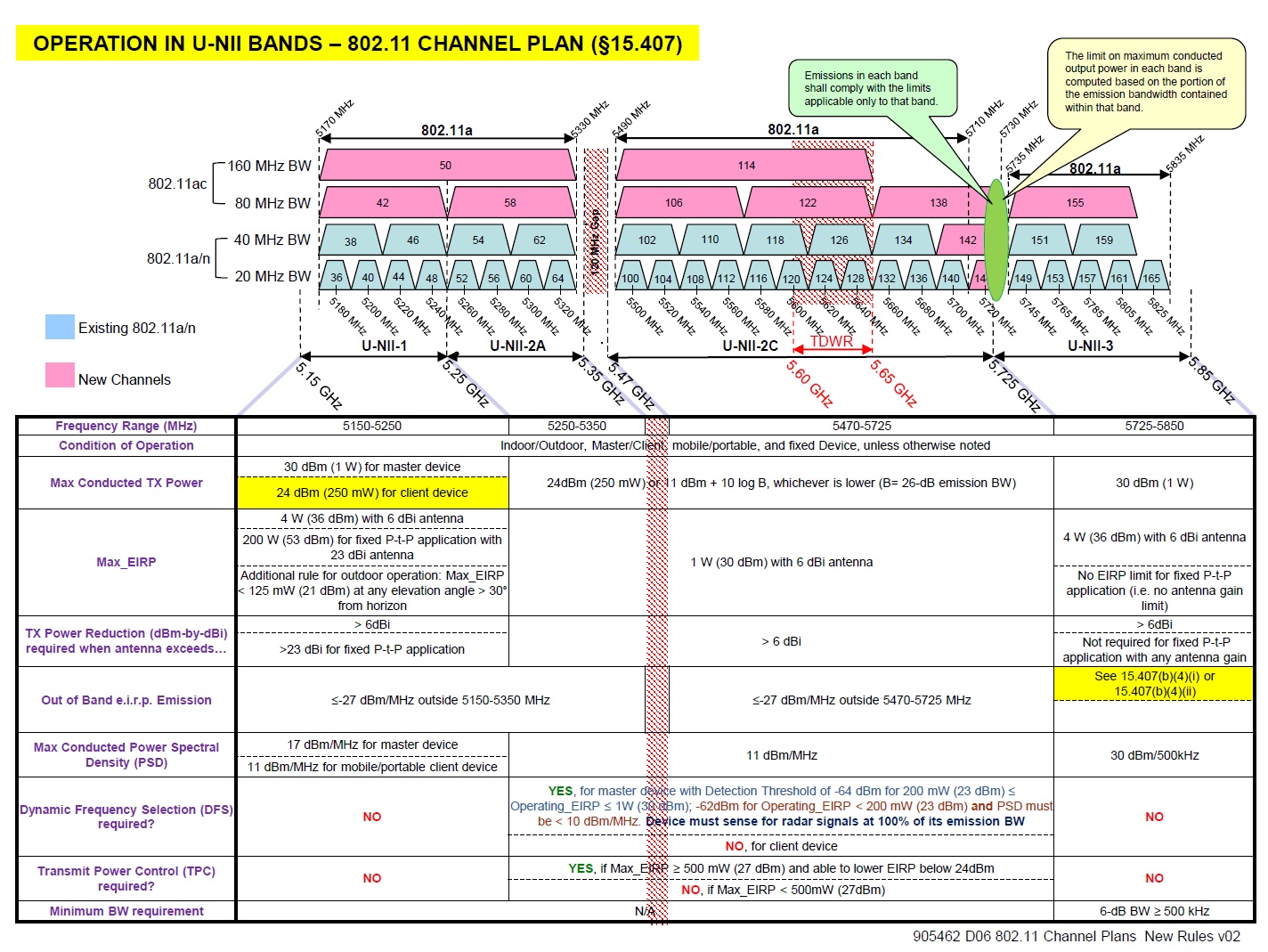

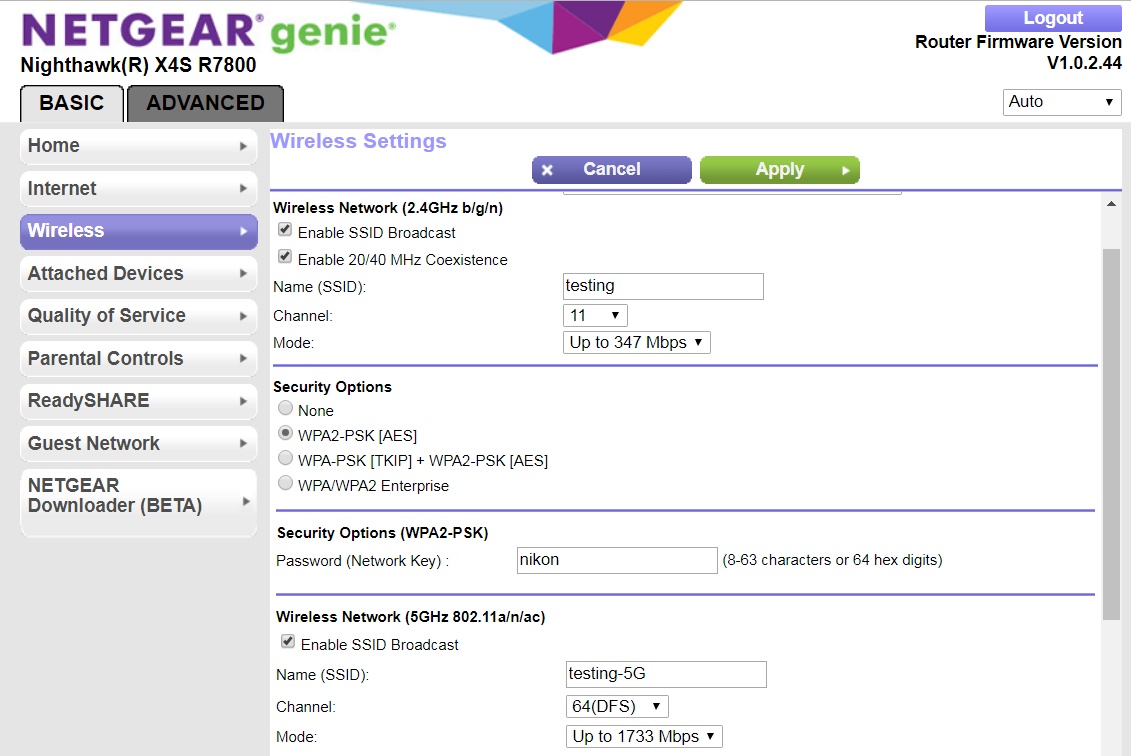

Spectrum: There is 560 MHz of spectrum (5170-5330, 5490-5730, 5735-5895 MHz) available for wifi to use in the U.S., supporting seven non-overlapping 80 MHz channels. If a device is labeled as supporting 802.11ac, you KNOW it also supports 80 MHz channels. BEWARE: Many entry-level low-end routers only support 180 MHz of the 5 GHz spectrum (not all 560 MHz). Channels: The 5 GHz wifi band has seven 80 MHz channels (see table right, bolded numbers; 42, 58, 106, 122, 138, 155, 171) BUT ONLY if you have an AP that supports ALL the new DFS channels. Channel Use Restriction: 16 (seen in red, right) of the 25 channels (or 64%) come with a critical FCC restriction (DFS - dynamic frequency selection) to avoid interference with existing devices operating in that band (weather-radar and military applications). Very few 'consumer-grade' access points support ALL of these 'restricted' channels, whereas many 'enterprise-grade' access points DO support these channels. More on this later in this section. 802.11h defines (1) dynamic frequency selection (DFS) and (2) transmit power control (TPC). Understanding 160/80/40/20 MHz channel selection: Your router will NOT present a list of the 160/80/40 MHz channels to you (eg: 42, 155). Instead, your router presents a list of ALL 20 MHz channels supported, and you select one channel as the 'primary' channel (and 20 MHz channel support). Then to support 160/80/40 MHz channel clients, the router just automatically selects the appropriate 160/80/40 MHz channels as per the table seen upper right. Channel 165: ONLY select channel 165 when the router is configured for 20 MHz channel widths. Because if you select channel 165 when the router is configured to use 160/80/40 MHz channel widths, there are actually NO available 160/80/40 MHz channels -- NONE! Wi-Fi clients will ONLY be able to connect to 20 MHz channel 165! This behavior was first noticed on a Netgear R7800 router.

With 5 GHz, neighbors can (often times) be on the same channel and typically not interfere with each other (nearly as much as 2.4 GHz), because with reduced range, neighbors can't see as many neighbors wifi anymore. Of course, all of this depends upon how 'close' your neighbors are. Protocol Overhead: The Mbps seen at the application level will be around 60% to 80% of the Mbps at the wifi (PHY) level. This is just due to wifi protocol overhead (see section on PHY client speed far above). New Channel Plan: Here is the 5 GHz 802.11 Channel Plan (see also below) from the FCC. Of note is that on April 1, 2014 the FCC changed the rules for usage in the 5 GHz band, to increase availability of spectrum for wifi use. Channel 144 was added (but older 5GHz clients will not be aware of this), power levels for channels 52 to 64 were increased, and other miscellaneous changes.

Helpful FCC reference documents: Here are some helpful documents RE spectrum usage:

Transmit Power: Channels 149-165 allow for both router/client to transmit at 1000 mW. Channels 36-48 allow for the router to transmit at 1000 mW (and clients at 250 mW). For all other DFS channels, both the router/client can transmit at 250 mW. However, this does NOT necessarily mean that channels 149-165 are the best channels to use (because everyone wants to use them). The 'reduced signal strength' for the other channels can actually be a huge advantage, because it means there is a much higher likelihood that you will NOT see neighbors wifi channels (as frequently as 2.4 GHz channels), which translates directly to less interference (the channel is all yours) and higher wifi speeds. Many residential routers have a transmit power around 995 mW. Many (battery powered) wifi clients have a transmit power anywhere from 90 mW to 250 mW. Client devices often transmit at power levels below the maximum power level permitted.

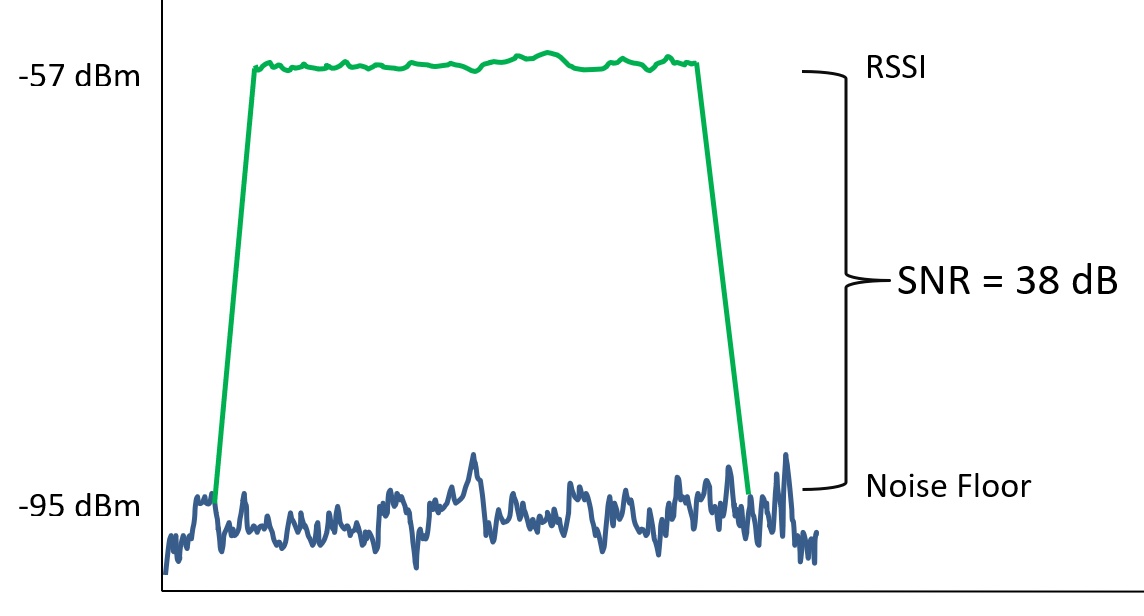

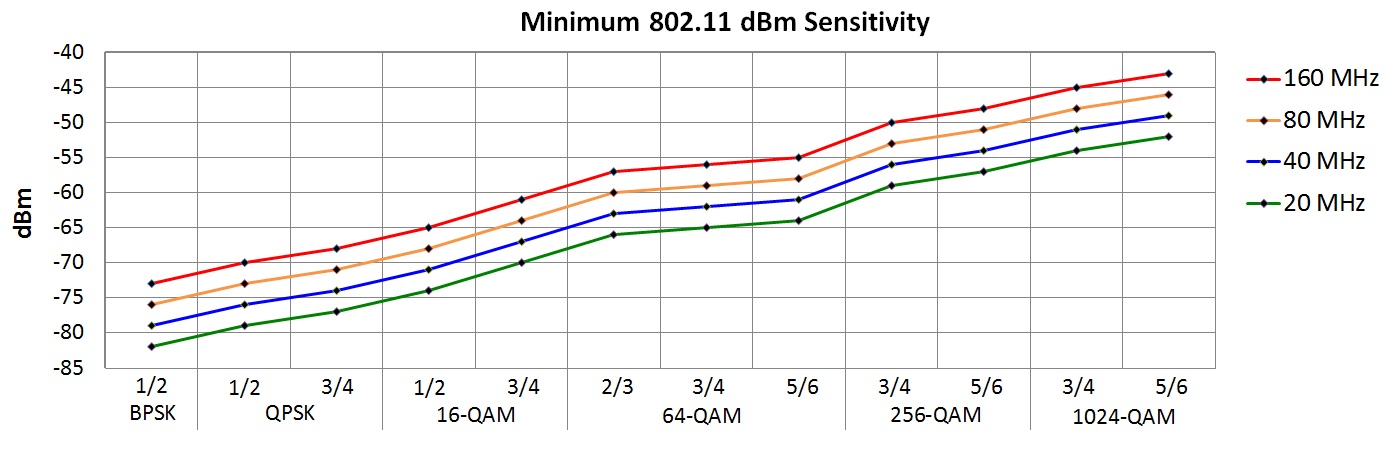

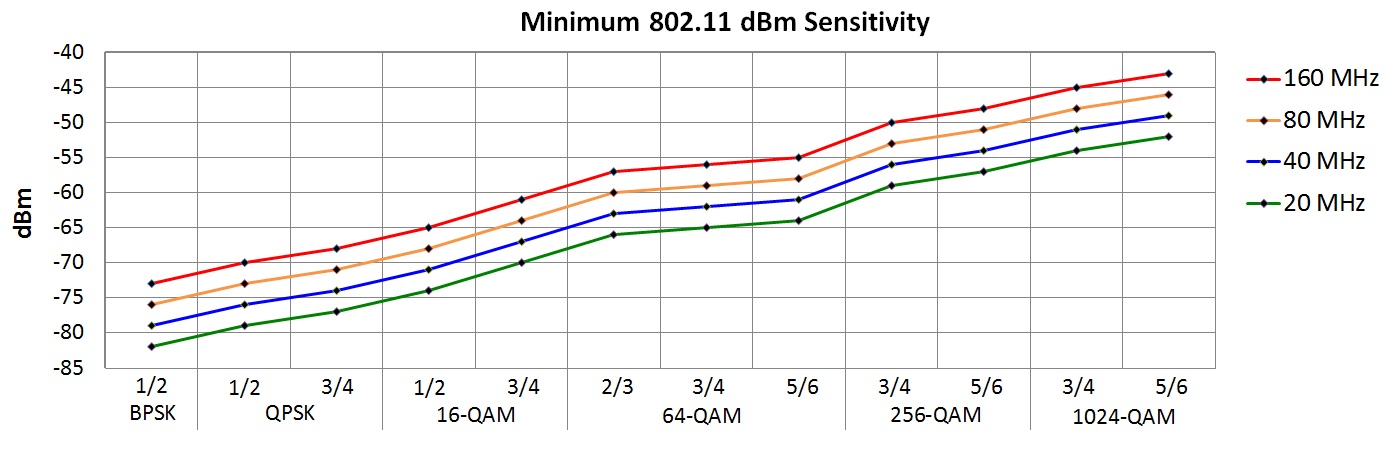

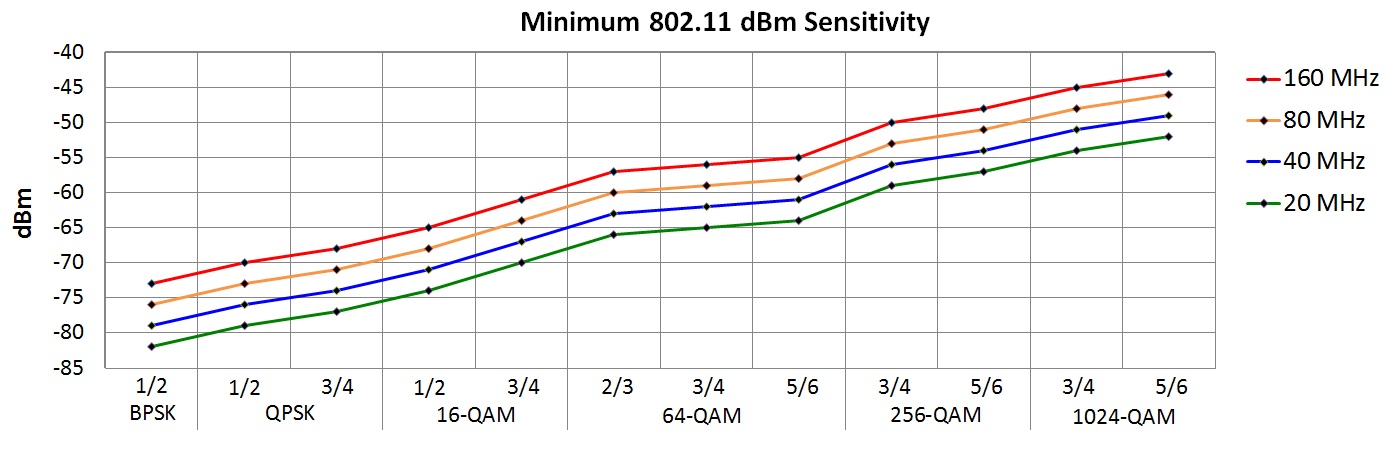

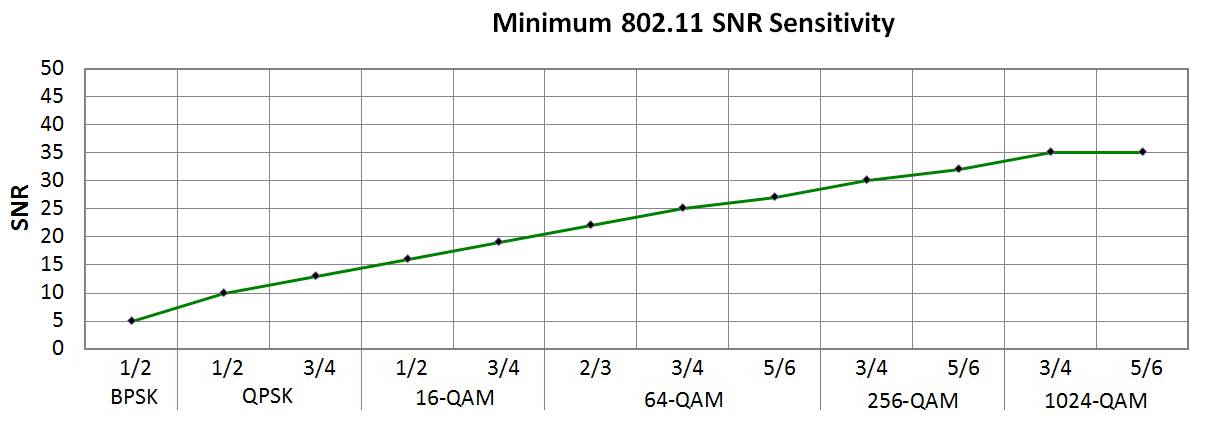

Another big thing is beamforming / more antennas: After playing around with a new 4×4 "wave 2" router (as compared to a 2×2 "wave 1" router), wow! A very noticeable increase in speeds at range. 802.11ac beamforming really works. Your mileage will vary depending upon construction materials. In one home (single level; sheetrock with aluminum studs), I saw a dramatic increase in speeds at range. But at an older second home with very thick brick walls, range improved just a little. 256-QAM: This modulation requires a very good SNR (signal to noise ratio), that is very hard to get with entry level routers. With a consumer-grade 802.11ac 2×2 "wave 1" AP I never got 256-QAM, even feet from the router. However, with a much higher quality 802.11ac 4×4 "wave 2" AP, I now regularly see 256-QAM 3/4 being used (at 25ft, through two walls). 1024-QAM HYPE: This modulation is a non-standard extension to 802.11ac, so most client devices will never be able to get these speeds. And even if you have a device that is capable of these speeds, are you close enough to the router to get these speeds? Understand that advertised speeds in these ranges are marketing hype. See Broadcom NitroQAM. 802.11ac Wave 2: The next generation (wave 2) of 802.11ac is already here. With feature like: (1) four or more spatial streams, (2) DFS 5 GHz channel support, (3) 160 MHz channels, and (4) MU-MIMO. Cisco Wave 2 FAQ. Buyer beware: Not all 'wave 2' products will support the restrictive 5 GHz DFS channels! WiFi certification for 'wave 2' only 'encourages' devices to support this -- so NOT required. Interference: It is a lot less common to find devices that use the 5 GHz band (vs the 2.4 GHz band), causing interference for wifi, but it is still possible. Just Google 'Panasonic 5.8 GHz cordless phone' for a cordless phone that uses the upper 5 GHz channels 153 - 165. FCC info on Panasonic phone. Minimum Sensitivity (dBM) for each MCS: Here is a graph of information that comes from the IEEE spec. Note that each time you double channel width, that there is a 3 dB 'penalty':  A final warning and caveat regarding 802.11n in 5 GHz: I have glossed over the fact that 802.11n can operate in the 5 GHz band, so DO NOT ASSUME that just because a device operates in 5 GHz that the device must be 802.11ac. That is NOT necessarily true. For example, the Motorola E5 Play (very low end) smartphone does NOT support 802.11ac, but does support dual-band 802.11n, so it connects to the 5 GHz band, but only using 20/40 MHz channels (in 1×1 mode), not the 80 MHz channels of 802.11ac, and not using 256-QAM. Another example: An older Dell laptop using Centrino Advanced-N 6230 dual-band wifi. The laptop 'sees' the 5 GHz SSID being broadcast from a 802.11ac router, but when the laptop connects to the router, it is only doing so using 802.11n, 2×2 MIMO, and 40 MHz channels (max PHY of 300 Mbps; no 256-QAM) Understanding where the speed increases in 802.11ac (over 802.11n) came from: 144 Mbps in 802.11n becomes 650 Mbps in 802.11ac by using an 80 MHz channel width (instead of 20 MHz channel width), which then becomes 866.6 Mbps via a new 256-QAM modulation. So quadrupling channel width is the key factor for increased speeds in 802.11ac over 802.11n. Technically, support for 160 MHz channels existed in Wi-Fi 5, but support in routers was spotty at best, and very rare in most client devices. Learn More:

★ The big advance in Wi-Fi 6 was (1) efficiently transmitting to a large number of users at the same time (but only for new Wi-Fi 6 clients, not prior wifi generation clients) and (2) 1024-QAM modulation. "The bottom line is until Wi-Fi 6 / 802.11ax clients reach critical mass, the benefits of 11ax are minimal and will have low impact." [Cisco] The key reason why: Wi-Fi 6 was designed from the ground up to provide speed improvements (HE: High Efficiency) to a group of Wi-Fi 6 clients as a whole, NOT an individual Wi-Fi 6 client!

2401 Mbps speed: The 2401 Mbps maximum PHY speed is for an 80 MHz channel to an 4×4 client. However, a much more realistic maximum PHY speed is 1200 Mbps for an 80 MHz channel to a 2×2 client (840 Mbps throughput), and for a realistic distance away from the router, a PHY speed of 864 Mbps (600 Mbps throughput).

The goal of Wi-Fi 6: The primary goal of Wi-Fi 6 is 'high efficiency' (HE). In a nutshell, Wi-Fi 6 adds 'cellular'-like technology into wifi. This was accomplished by changing to the OFDMA modulation scheme and changing the wifi protocol to directly support many users at once. The result is greatly improved overall (aggregate) capacity in highly 'dense' (lot of devices) environments (like schools, stadiums, convention centers, campuses, etc). Multi-user support is baked into OFDMA: This is a critical concept to fully understand about Wi-Fi 6. In Wi-Fi 5, 'multi-user' was accomplished via MU-MIMO using multiple antennas. HOWEVER, in Wi-Fi 6, there is a SECOND (and now primary) 'multi-user' method 'baked' into the protocols called MU-OFDMA. Don't confuse MU-OFDMA with MU-MIMO! Also, see this interesting MU-OFDMA vs MU-MIMO article. MU-OFDMA (Multi-User OFDMA): The efficiency gains in 802.11ax primarily come from using OFDMA in 'dense' (lots of users) environments -- breaking up a channel into smaller Resource Units (RU) -- where each RU is (potentially) for a different user. There are up to 9 users per 20 MHz channel (so up to 36 users per 80 MHz channel). So, 802.11ax has high efficiency multi-user transmission built into the protocol, meaning that the user must be 'Wi-Fi 6' to take advantage of this. Capacity to a large number of users at once (as a whole) should dramatically increase (the design goal of 802.11ax was a 4x improvement). This multi-user support is a big deal, and will greatly improve wifi for all -- but it will take many YEARS before most clients are 802.11ax. So don't expect to see Wi-Fi 6 benefits for YEARS. But what about peak speed to ONE user: Please note that 'peak' speed (one user using the entire channel at distance) changes very little (around 11% improvement over 802.11ac). So, if you are looking for much higher Mbps download speeds (benefiting just one user), 802.11ax is not the solution (eg: PHY speed at 256-QAM 3/4 in 802.11ac of 780 Mbps changes to 864 Mbps in 802.11ax). Instead, find a way to increase the MIMO level (or channel width) of the one user. The goal of every prior version of wifi was dramatically increasing 'peak' speeds (for one user). And by looking at Wi-Fi generation Mbps speeds, you can see this: 2 -> 11 -> 54 -> 217 -> 1733 -> 2401, except for the last jump, which is Wi-Fi 6. Instead, by changing to MU-OFDMA in Wi-Fi 6, there will be dramatic (overall) capacity gains to a dense set of users (as a whole), but only when (all) clients fully support Wi-Fi 6.

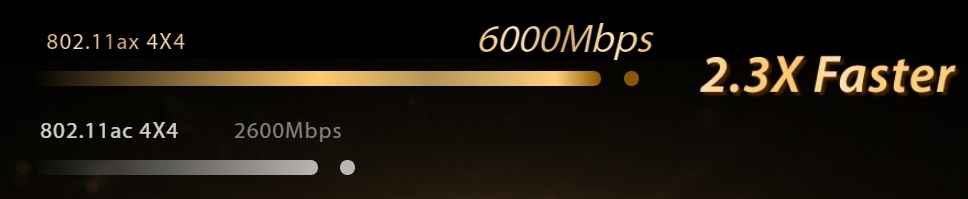

1024-QAM: This higher order QAM is now officially part of the standard, but you will need to be very close to the router/AP to get this QAM. Also, this modulation can only be used when a client is using an entire 20-MHz (or wider) channel -- so NOT available for small RU's. In order to achieve 1024-QAM, you will need an excellent signal (be very close to the router). Note that each time you double channel width, that there is a 3 dB 'penalty':  Channels: The channels in Wi-Fi 6 are exactly the same as the available channels in Wi-Fi 4 and Wi-Fi 5. However, since there is so much more spectrum in 5 GHz than 2.4 GHz, what matters the most for Wi-Fi 6 are the channels in 5 GHz. Channel Width: Unlike 802.11ac, which required clients to support 80 MHz channels, 802.11ax permits 20 MHz channel only clients. This was done to better support low-throughput low-power IoT devices (eg: those devices powered by battery) that would take a range/power hit using wider channel widths. 160 MHz channels: Support for 160 MHz channels in some routers reduces MIMO support. For example, in Netgear's RAX120, there is 8×8 MIMO support for 80 MHz channels, but only 4×4 MIMO support for 80+80 channels. The other problem with 160 MHz channels is that there are currently only two channels, and they both intersect with DFS channels (making them both potentially unusable). Bands: Technically, 802.11ax does also operate in 2.4 GHz, but since there are NO 80 MHz channel there, most people (especially home installations) will stay in 5 GHz. It has been said that 802.11ax is in 2.4 GHz mainly for the benefit of IoT device support, but it remains to be seen if that will happen at all -- as most low power IoT devices stuck with Wi-Fi 4 and never even implemented Wi-Fi 5. 6 GHz spectrum: The FCC opened up the 6 GHz and for Wi-Fi (but this requires new hardware). See Wi-Fi 6E in the next section. WPA3: For a device to be Wi-Fi 6 'certified', it was announced that WPA3 support is a mandatory feature. Works better outdoors: 802.11ax changed symbol timings (from 3.2µs to 12.8µs; and increased GI times), which allows for wifi to operate much better in outdoor environments, where signal reflections take more time and can cause problems. The increased timings account for these reflections. HERE COMES THE HYPE: Manufacturers are touting incredibly speed claims regarding 802.11ax (immediately below). However, we know that an 802.11ac 2×2 client at 256-QAM 3/4 has a PHY speed of 780 (see table above section). And with 802.11ax (and everything else the same), the PHY speed is 864 (see table immediately above). YES, that is better by a little (11%), but not nearly as much as you are led to believe.  Very deceptive router manufacturer speed comparison The above "2.3X" above is comparing 'apples to oranges' -- different channel widths and different modulation+coding, and combining the total of two bands (2.4 GHz and 5 Ghz). When you compare 'apples to apples' the raw PHY speed advantage of 802.11ax over 802.11ac is only 11%. Analogy: It should be painfully obvious by now that router manufacturers are selling you on hype. They are selling you on a 'dragstrip' (the router), where you can 'legally' go '1000 mph' -- and that sounds fantastic, so you buy the dragstrip (router). But then you step back and realize that (1) all the vehicles (wifi devices) you own don't go over 120 mph, (2) you can buy faster cars but they are not legal for you (desktops have faster wifi than smartphones), and (3) 1000 mph was obtained by adding the speeds of multiple cars together (aggregating multiple wifi bands). Should I upgrade to Wi-Fi 6? For a business, 'maybe'. If you have a small to normal number of wifi users connected, Wi-Fi 5 will work just fine. But if you have a large number of Wi-Fi 6 users, then you may very well see an improvement by using Wi-Fi 6. Is there really something that you can't do with 455 Mbps throughput in Wi-Fi 5 that you can all of a sudden do with a little (10%) more throughput in Wi-Fi 6? A final word on Wi-Fi 6: Is it possible to get a 38% speed improvement over Wi-Fi 5 to a single wifi client? Yes, but you have to be a Wi-Fi 6 client very close to the Wi-Fi 6 router so that the highest 1024-QAM can be used. And 'at range', other Wi-Fi 6 clients will see a speed improvement lower than that (closer to 11%). For Wi-Fi 5 clients, no speed improvement will be seen. For some people, maybe this small percentage increase matters. But if ultimate speed matters that much to you, just plug into Gigabit ethernet! I have seen some reviewers show graphs showing a huge increase in Wi-Fi 6 speeds as compared to Wi-Fi 5, but that result was obtained by using 160 MHz channels in Wi-Fi 6 vs 80 MHz channels in Wi-Fi 5. When reviews show numbers too good to be true, scrutinize the details. Regardless of what I and others say, be informed with the facts (and not hype) and make your own (fully educated) upgrade decisions. Look at your PHY speed before and after a router upgrade and decide for yourself if the change was worth it. If your client device is in the same room as a Wi-Fi 6 wireless router, you may see a big speed boost using Wi-Fi 6 over Wi-Fi 5. But once you move to the next room, you will only see a very subtle speed boost. I actually think Wi-Fi 6 is going to (eventually) be great. But the industry selling Wi-Fi 6 routers that are actually 'draft' routers that don't fully implement the Wi-Fi 6 specification, and are not Wi-Fi 6 certified, is a problem. The router industry has not self-regulated, and you, the consumer, are paying the price. Fully "Wi-Fi 6 Certified" routers ARE just starting to come out. Be patient and don't buy a 'draft' router. Understanding where the speed increases in 802.11ax (over 802.11ac) came from: 866.6 Mbps in 802.11ac becomes 960.8 Mbps via the switch to OFDMA, which then becomes 1201 Mbps via a new 1024-QAM modulation. When very close to the router, 802.11ax can be 39% faster than 802.11ac. But 'at range', 802.11ax is only 11% faster than 802.11ac (for a single client). UPDATE March 2022: If you have a brand new Wi-Fi 6 client device and a brand new Wi-Fi 6 router and are using both in the same room (and both devices are very close to each other) there is a high likelihood that the two devices will negotiate an initial 160 MHz channel width (for non-Apple devices only). Throughput can be as high as 80% of the 2401 Mbps PHY speed (or around 1900 Mbps) -- which is very nice! However, this only happens when the client device and router are very close to each other (in my testing, four feet away) -- and once you start adding distance or walls, the two Wi-Fi 6 devices will 'slow down' significantly and communicate with each other at much closer to Wi-Fi 5 speeds. Technically, Wi-Fi 5 also supported 160 MHz channels, but it was rare to see a battery powered client device support 160 MHz channels. For some reason, that appears to have changed in Wi-Fi 6, where support for 160 MHz channels (even in battery powered client devices) now appears very common (but not for Apple devices). Learn More:

★ The big advance in Wi-Fi 6E is a TON more spectrum/channels (the entire 6 GHz spectrum) -- adding 14 new 80-MHz channels! This makes 160 MHz channels actually usable and commonplace -- instantly doubling throughput over the prior Wi-Fi 5/6 with 80 MHz channels.

There is only 560 MHz of spectrum currently available to Wi-Fi in 5 GHz (and only 70 MHz in 2.4 GHz). So adding an additional 1200 MHz in 6 GHz is a very welcome and significant jump in spectrum.

The big deal: TONS of new spectrum! The additional spectrum allows for 14 additional 80 MHz channels (or seven additional 160-MHz channels) in wifi, which means the chances of sharing spectrum with another device/neighbor will be greatly reduced. You should then have your own 160 MHz channel all to yourself, potentially doubling throughput (vs an 80 MHz channel). Many entry-level Wi-Fi 5 routers (with no DFS support) only support 180 MHz of spectrum. But I expect entry-level Wi-Fi 6E routers (with no AFC support) to support all 1200 MHz of spectrum. The gotcha: New hardware (routers/clients) will be required. Current Wi-Fi 6 devices don't support Wi-Fi 6E!

Low-power mode: In 'low-power' mode, access points are permitted to use the entire 1200 MHz of spectrum with no AFC restrictions, but range is less (and is an unknown right now until tests are performed on real hardware), and use is restricted to indoor use only. Wi-Fi 6E access points in low-power mode are permitted to operate at 24 dBm EIRP (6 dB BELOW 5 GHz DFS power levels), and Wi-Fi 6E clients at 18 dBm EIRP (6 dB BELOW that of the AP). Many Wi-Fi 5 clients today already operate 'around' this power level, so Wi-Fi 6E range will be affected by the slightly higher operating frequencies, and the 6 dB power difference (below DFS). Namely, expect Wi-Fi 6E range (in low-power mode) to be around 42% of Wi-Fi 5 DFS channel range. Normal-power mode: In normal power mode, access points are only permitted to use 850 MHz of spectrum (see table right), but are required to use something called AFC (see below), which requires the access point to report its geo location (GPS), as well as serial number to a centralized database. It remains to be seen if customers will accept this 'invasion of privacy'. Wi-Fi 6E access points in normal-power mode are permitted to operate at 36 dBm EIRP (the same power levels of 5 GHz U-NII-1 power levels), and Wi-Fi 6E clients at 30 dBm EIRP (6 dB BELOW that of the AP). Most Wi-Fi 5 devices already operate below these levels, so Wi-Fi 6E range will be affected only by the slightly higher operating frequencies. Namely, expect Wi-Fi 6E range (in normal-power mode) to be around 83% of Wi-Fi 5 range. Automated Frequency Coordination (AFC): The FCC docs extensively discuss an 'Automated Frequency Coordination' (AFC) system to avoid conflicts between existing licensed use (point to point microwave) and new unlicensed devices (access points). It appears that the FCC has settled (May 26, 2020) on a centralized AFC system whereby an access point must contact the AFC "to obtain a list of available frequency ranges in which it is permitted to operate and the maximum permissible power in each frequency range". But in order for this to work properly, the access point MUST report its geo-location (eg: GPS location), as well as antenna height above the ground, to the centralized AFC system. The FCC will also require the 'FCC ID' of the access point, as well as the serial number of the access point. Privacy mitigating factors: An access point can operate in 'low power mode' and then NOT be subject to AFC (but then signal range WILL suffer) OR, the access point can reduce the GPS quality and then report a larger general 'area' to the AFC instead of an exact location (but then frequencies and power levels that can be used might be reduced). A major concern: Range: A major concern is what range will be for Wi-Fi 6E devices. Based upon raw specifications, range will be reduced over what is possible in 5 GHz. Only time will tell -- until actual Wi-Fi 6E devices become available for testing. Another concern: the spectrum is already heavily used: The 6 GHz spectrum that the FCC wants to open up (for unlicensed Wi-Fi use) is already being "heavily used by point-to-point microwave links and some fixed satellite systems" (source) by existing licensed services. So, it remains to be seen how many channels can actually be used in real-life with AFC for normal-power devices. Incumbent Services: The FCC did not just have 1200 MHz of spectrum laying around unused. Instead, this spectrum is heavily used by 'incumbent services', such as: Best use case: The first wave of Wi-Fi 6E devices will likely operate in only 'low-power' mode (as no AFC is required and the entire 1200 MHz can be used; but restricted to indoor use only), but range will be reduced. When combined with effective range decreasing with channel width, the best use case for Wi-Fi 6E 160 MHz channels is between two devices in the same room. The thinking is that with Wi-Fi 6E and 160 MHz channels, a reliable 2 Gbps PHY connection with 1 Gbps actual throughput becomes commonplace (instead of hit or miss) when are you in the same room as the access point -- with only a 2×2 MIMO client device. Interesting observations about Wi-Fi 6E from this FCC doc:

Moving fast: Wi-Fi 6E was just announced as an idea/desire on January 3, 2020. Days later, Broadcom announced chipsets supporting Wi-Fi 6E in 6 GHz. Then on April 24, 2020, the FCC moved forward in supporting this (summary). And all other major chipset vendors have also announced support for Wi-Fi 6E. Wi-Fi 6E products exist right now, but some are expensive. Just be patient. Understanding the speed increase: There is no speed increase in Wi-Fi 6E over Wi-Fi 6. Instead, Wi-Fi 6E makes 160 MHz channels much more commonplace (vs 80 MHz channels).

★ The big changes that are expected to be introduced in Wi-Fi 7 are:

Please note that Wi-Fi 7 routers will only benefit Wi-Fi 7 clients (not Wi-Fi 4/5/6 clients). And once you do actually have Wi-Fi 7 clients, there is very little point in upgrading your router to Wi-Fi 7 if you are not currently noticing any speed issues. Give Wi-Fi 7 technology time to mature. The benefit for Wi-Fi 7 will be mainly for devices that are 'near to' (in the same room) as the router/AP -- expect a maximum PHY speed of around 4.8 Gbps for a 320 MHz 2×2 channel. Understanding the speed increase: Wi-Fi 7 will make 320 MHz channels commonplace, instantly doubling throughput over the 160 MHz channels in Wi-Fi 6.

This section applies to Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac), Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax), and Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be) operating in 5 GHz, but not Wi-Fi 6E (802.11ax) operating in 6 GHz. In a nutshell: If you buy a router that does not support DFS channels, you are limited to only having TWO 80 MHz channels available in 5 GHz (instead of SIX channels), greatly increasing the likelihood of sharing that channel with others (a close neighbor) -- meaning that you are sharing bandwidth. If your router supports DFS channels, your likelihood of being on your own channel all by yourself is much higher -- meaning all channel bandwidth is yours. UPDATE: Beware that some very inexpensive routers might only support a SINGLE 5 GHz channel. Just do your reserach before purchase!

Background: There are SEVEN core 80-MHz wifi channels in 5 GHz. Two channels can always be used (green highlight, right), ane one is new as of 2019 (and for indoor use only). But, for the other four DFS channels to be used, a router must include special processing to avoid interference with existing usage (weather radar and military applications; red highlight, right) and pass FCC certification tests. DFS = Dynamic Frequency Selection Why DFS support is important: Support for all channels becomes critically important to avoid interference (sharing bandwidth) with a neighbor's wifi. Ideally, every AP/router (yours and neighbors) should be on a unique/different wifi channel. Also, this is especially important if you can see several other 5 GHz AP's, which happens when you (1) have close neighbors like in an apartment building, or (2) want to install multiple AP/routers. So, only consider AP/routers that support ALL the DFS channels. Range: An AP/router for DFS channels has a transmit power limitation of 250 mW (vs 1000 mW for non-DFS channels). However, this rarely limits range to clients, as virtually all client devices already transmit at less the 250 mW for ALL 5 GHz channels (so the client device limits range, not the AP/router). Avoid AP/routers with NO DFS channels: It is very common to find 'consumer-grade' routers that support NONE of the DFS channels (they only support TWO channels). Buyer beware. Also beware brand new routers with NO DFS channel support, as the vendor may not release a firmware update that adds support for these DFS channels (don't buy a device on the hope that DFS support will be added later via a firmware update). Some vendors have NO routers that support DFS channels. Some 'consumer-grade' AP's DO support some DFS channels: Some consumer grade routers DO support some or all of the DFS channels. Just do your research. Netgear ALERT: Most Netgear routers don't support 80 MHz channel 138. But this is slowly changing. The R7800 is a rare exception, supporting channel 138, but only via firmware 1.0.2.68. Also, it appears that Netgear is finally 'aware' of the issue as some of the newer 'AX' hardware also supports channel 138. Some business-grade AP's DO support 5 GHz DFS channels: Some business-grade 5 GHz devices DO support the DFS channels, so you get the full advantage of a LOT more channels in 5 GHz. Most of the Netgear business access points (Netgear ProSafe Access Points) do NOT support the restricted 5 GHz channels. But I did find ONE that did. Just do your research. Many Enterprise-grade AP's DO support 5 GHz DFS channels: According to this data sheet ALL of the Ubiquiti UniFi AC models (802.11AC Dual-Radio Access Points) are DFS certified. For example, I was in a Drury Hotel and from my room, I could see the Drury SSID on channels 48, 64, 100, 104, 108, 140. So the hotel was clearly using DFS certified 5 GHz access points -- successfully. Beware some 'best router' reviews: Watch out for 'best router' reviews online that select a 'best overall' router that do NOT support ANY DFS 5 GHz channels (only TWO channels supported).

How to research DFS support for any router/AP (check the FCC filings):

DFS Master/Slave: When looking at FCC filed documents, look for and open up the "Test Report (DFS)". The report will then talk about the EUT (Equipment Under Test) being certified as a 'Master' or a 'Slave' (or both). Master means a router/AP (broadcasts a SSID) and Slave means a device that connects to a Master (wifi client). A device is not allowed to use any DFS channels unless the proper paperwork is filed with the FCC. Netgear was plain lazy: Netgear got the R6700v3 certified as a DFS Master but failed to get the router certified as a DFS Slave. This matters if you use the R6700v3 as a 'wireless bridge' (to connect 'ethernet only' devices to your main wifi router), because all of a sudden, in that mode, the R6700v3 no longer supports DFS channels -- meaning that if you bought the R6700v3 to connect to your main router (broadcasting/using a DFS channel), the R6700v3 will NOT work! Warning: Just because a router allows DFS channels does not mean DFS channels can be used: Be aware that when a DFS channel is selected, the router MUST look for conflicts on that frequency, and if a conflict is found, the router must automatically change the channel (likely to a non DFS channel). You won't know until you try. Often times, one or two of the DFS channels can not be used (but the other DFS channel can). And each physical location is different. You won't know until you try. I have even selected a DFS channel and seen it work for weeks, only for the router to then all of a sudden auto select a non-DFS channel (meaning the router detected a conflict). Was this a real radar signal detected, or a false alarm (most likely)? You just need to be patient finding a DFS channel that works long-term for you. Warning: Not all wifi clients are DFS capable! All of the above is discussing DFS support in routers, because that is where ALL of the hard work takes place (like scanning for radar, etc). Wifi clients have it easy -- just follow the lead of the router. And yet, it is possible that a wifi client never got DFS certified, and therefore is NOT permitted to use DFS channels, and can NOT connect to a router using any DFS channel. A wifi client not supporting DFS channels is very rare -- and is definitely incredible laziness on the part of the device manufacturer. Often times, you will never notice, because the problem device will just connect to the router's slower 2.4 GHz band (not the fast 5 GHz DFS band).

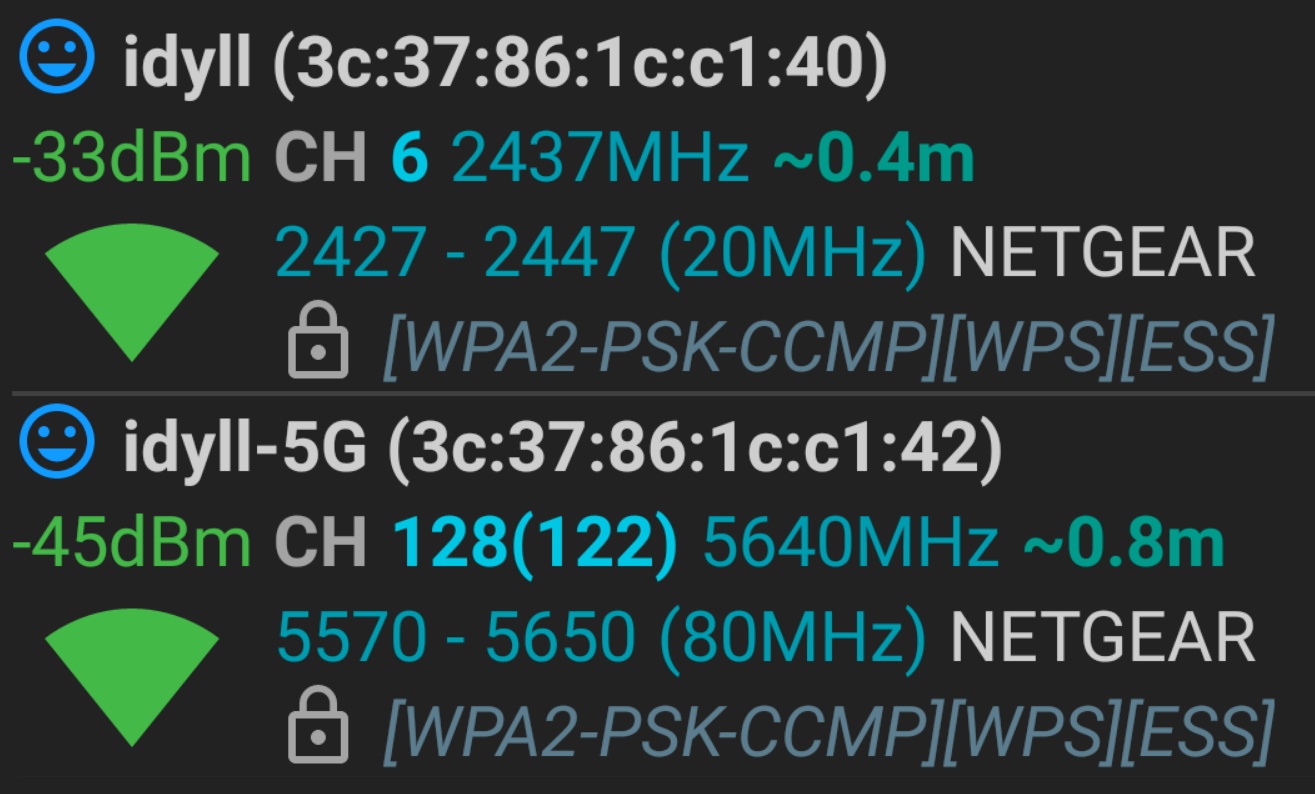

SSID: SSID is simply the wifi network NAME. When you connect to a wifi network in a client, you must select this network name (called SSID). At home, you typically will only have one router with that ONE network name. However, if you add another wifi access point, you want it to use the SAME network name (and password + security), as this allows for wifi roaming. Your wireless devices simply connect to the strongest wifi signal with a matching SSID name. You can use different SSID names, but then you don't get wifi roaming. 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz SSID names: There is a big debate -- should your 2.4 GHz band network and 5 GHz band network have the SAME SSID names, or different names (often with a "-5G" appended to the 5 GHz band SSID name)? If named the same, client devices choose which band to connect to. If named differently, the end user must choose which band to connect to. The problem with the 'same name' technique is that some client devices are 'dumb' and incorrectly connect to the 2.4 GHz band instead of the 5 GHz band (and then speeds are much slower than they should be). I had this problem with a laptop that would initially start out connected to the (fast) 5 GHz band, but after about 10 minutes, it would then switch to the (much slower) 2.4 GHz band (for unknown reasons). Yes, the 5 GHz RSSI signal was weaker, but throughput from 5 GHz was MUCH better. I fixed by appending a "-5G" to the 5 GHz band SSID. Disabling 'SSID Broadcast' is NOT a form of security: Do not think that disabling 'SSID Broadcast' will improve the security of your wireless network. It will not. Because anyone with the right tools can still see your network and find out the network name. Because any client device connecting to your network must include the SSID name in the 'I want to connect' request, that any Wi-Fi sniffer can capture and then see. BSSID: This is the MAC address of the AP that your client actually connects to (because you can't tell which AP you connected to from only the SSID). This is very useful when you have more than one AP using the same SSID, because the BSSID identifies the unique AP that you actually connected to (a must for debugging).

Channel: ALL wifi access points (in your house and visible neighbors networks) covering the same frequency must share the wifi bandwidth. Because of this, assign channels 1, 6, 11 (2.4 GHz) and 42, 58, 106, 122, 138, 155 (5 GHz) to your APs in a manner to best avoid conflicts (with yourself and neighbors). There is nothing special about channel selection. Analogy: A channel is like a lane on an Interstate highway. All cars (AP) can use the same lane (channel), but that is slow and inefficient (lanes go unused). Everything works best when cars (AP) use all lanes (channels) -- as evenly as possible. TIP: Static IP Addresses: In your main router, assign a fixed (static) IP address to IoT devices that are always connected to your network. This actually works around some known connectivity bugs in IoT devices (eg: Ring cameras) that go into a 'deep sleep mode' in order to extend battery life, but this sometimes causes the router to not 'find' the device (an ARP issue). Assigning a fixed known IP address allows the router to always 'find' the camera, even when the camera is in 'deep sleep' mode.

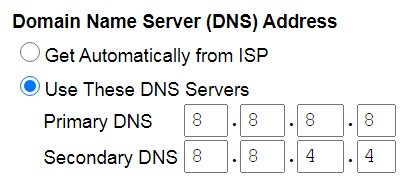

DNS Servers: I configure all of my routers to use Google's Public DNS servers at 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4. In your router, the setting for DNS servers is usually found in the 'Internet Setup' section. Another fast DNS service is provided by CloudFlare, with DNS servers 1.1.1.1 and 1.0.0.1. The default DNS setting is typically 'automatic' (so, use the ISP's DNS servers). But the problem with an ISP's DNS servers is that they (1) can be slow, (2) often improperly redirect on DNS errors (like 'server ip can not be found') to some 'self-promotion' web page (and this can cause some software programs that reply upon 'not found' DNS replies to fail -- not good), and (3) frankly, sometimes work incorrectly (violate TTL rules). When you make this change, all devices locally on your network will automatically use the new DNS servers (except for those devices that manually override the 'get automatically from the router' behavior). Turn UPnP OFF: There have been so many security vulnerabilities in "Universal Plug and Plug" in routers over the years, that the first thing you should do is turn UPnP off. Then just see if everything in your network still works (it will for most people). If so, great. But if not, then consider maybe turning UPnP back on (or manually fixing what stopped working). Change the router password! Change the 'administration' password on your router! You don't want a guest (or hacker) gaining easy access to your router and making changes. I am surprised how often I visit a vaction home only to find the router set to default credentials (often 'admin/password'), which opens up the router to unauthorized changes. Do NOT touch 'Enable WMM': "Enable WMM" is ON by default on ALL routers, because it is actually needed for any speed past 54 Mbps. Turn if off if you want to see what I mean. Firmware updates: If your router does not update firmware automatically, stay on top of keeping the firmware up-to-date, as there are security vulnerabilities fixed all the time.

Are Wi-Fi speeds 'at range' not as fast as you would like? So, how do you go about improving Wi-Fi speeds?

The HARD way: The 'hard way' is to try to improve the Wi-Fi network that you already have. Wi-Fi is a TIME shared resource. So, the goal for improving things is to get every wifi client to use that resource in as little time as possible, especially those few devices that are 'heavy users'. So, target the 'heavy users' first with the goal being to 'free up wifi time' for other wifi users:

Consider these options...

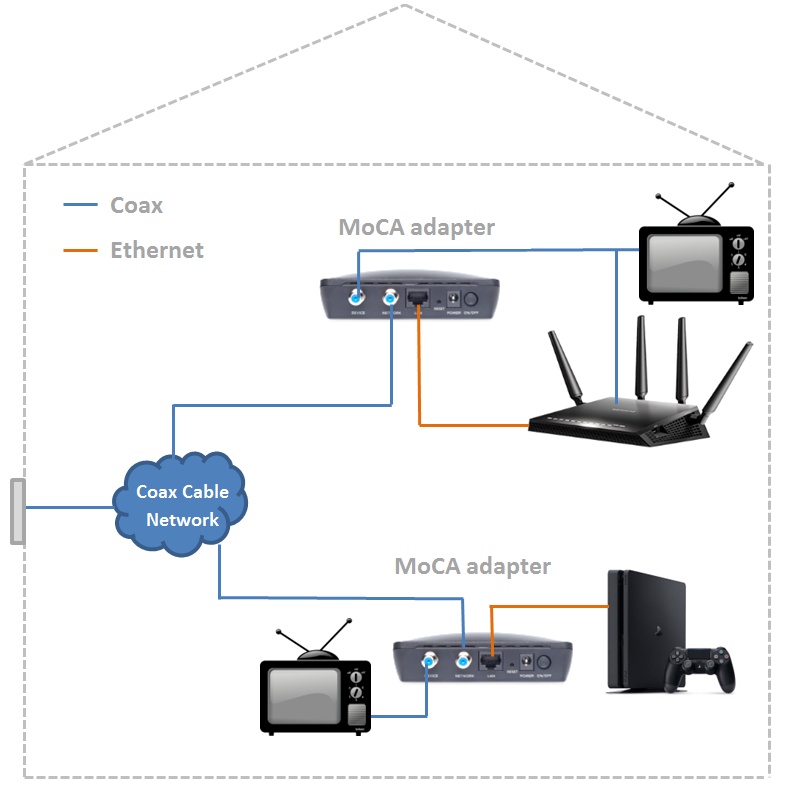

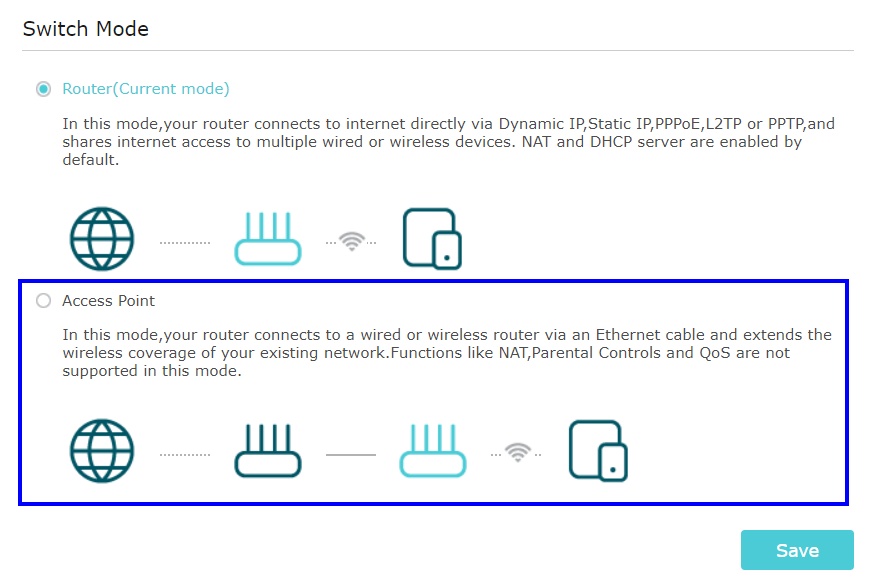

Remember that everything is about TIME on the channel: It all comes down to 'time' spent on the wifi channel -- So target the devices that spend the most time on the wifi channel, and conversely, don't worry about (ignore) low channel width, low PHY devices, that don't use wifi that much (eg: thermostat). The worst 'time' offenders will be high internet usage devices with low PHY rates -- so target those devices first. First, analyze the client devices that download/upload the most data. They should be running at high PHY speeds; and if not, fix. First, did PHY speed increase?: Always check the PHY speed of your client devices both before and after an upgrade to confirm that there was an actual improvement in PHY speeds. Otherwise, there was no point in upgrading. Next, did throughput increase?: Improving PHY speed is the first step. The second step is a throughput test to verify overall speeds increased. Why? Because you could have the best PHY speed ever, but if you are sharing that channel with others (a heavy usage neighbor), overall speeds could go down. A good way to test wifi throughput is by transferring a file from one PC (wired) to another PC (wireless) and looking at the OS provided network utilization graphs. Or, better yet, use a dedicated SpeedTest program. The easy way (restated again): One of the fastest, easiest, and BEST ways to dramatically improve Wi-Fi speeds to 'the maximum speed possible' is to install a brand new recommended router (configured as an access point and wired/Ethernet back to the main router) in the same room where you want to improve Wi-Fi speeds. Wi-Fi works best when the Wi-Fi signal does not have to go through walls/floors/etc and does not have to travel too far.